History of Newcastle Rowing Club

Part 1 - Rowing in Colonial Australia (continued)

Part 1 pages: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7

Boats

Countless types of boat were in general use during the colonial era. Even within each class there were differences in shape and dimensions. Boats predominately used in rowing contests were dinghies, skiffs and gigs. Dinghies were used by youths pulling a pair of sculls, skiffs were used with a pair of sculls, two pair sculls (double) or pair of oars (pair). Gigs were pulled by four oars or four pair sculls (quad). Information on boats commonly used for racing is contained in Appendix A. Depending on availability and rower interest, a variety of other ship's boats such as cutters as well as butcher boats (discussed below) and lighters were used occasionally in races on Newcastle Harbour in the 18th and early 20th century. Even though Newcastle is not usually associated with the whaling industry, a race for whaleboats was included in some regattas on Newcastle Harbour from at least 1857 with spasmodic appearances until 1912.

Built of timber, these early boats were heavy, wide, clinker built, inrigged and with fixed seats, a moveable footboard, thowle rowlock and exterior keel.

Virtually all boats used in early races for pairs/doubles and upwards included a coxswain. An obvious benefit of the cox was that he (in those days, it was always a 'he') could steer the best possible course, particularly where there were alignments changed such as courses with bends or turns. It was only at the start of a race at Henley in 1868 that the cox of one boat, thought by the coach to be unnecessary, jumped overboard. This selfless action that initiated coxless rowing resulted in an easy win and inevitable disquallfication. Although a coxless boat being lighter is faster (theoretically anyway), the use of a cox in boats used in skiffs with two pair sculls persisted well into the 20th century, e.g. 1931 at Stockton.

Predecessors of the modern eight (the pride of any fleet) originated in inter-university contests in England in the early 1800s. They appear to have been based primarily on eight-oar cutters although the whale boat was emulated by some designers. By the middle of the nineteenth century eights were 56 - 60 ft long with a beam of 23 - 24 inches. Gradually they became longer (up to 66 ft) and narrower although there was debate about the optimum length, whether 55 ft or 63 ft or in between.

Eights, were rowed by Sydney clubs from about 1878, primarily because they were used by NSW crews in inter-colonial 8-oared contests. Records suggest eights were not used by any club or regatta in the Newcastle region until late in the 20th century.

Butcher Boats

No discussion on rowing in Newcastle during the sailing era would be complete without mention of 'butcher boats'.

For those who lived during the sailing era, everyday reliance on rowing was accepted as normal. In Newcastle, 'butcher boats' (so-called because of their use initially by, you guessed it, butchers) provided an especially colourful chapter in Newcastle's rowing history. The term was later applied to boats used for the same purpose by other merchants.

Manned by expert rowers called "runners", butcher boats travelled long distances off the coast in all conditions to meet incoming vessels from overseas to gain the ship's order for fresh meat. Runners primarily operated from Newcastle and Sydney as these were the principal destination of such shipping. As the number of ships probably numbered in the thousands, it was a lucrative way of gaining business. Butcher boats were also widely used in the Northern Rivers area of New South Wales where they were used on local rivers to deliver meat.

It was a dangerous and competitive occupation where being the first to meet an incoming vessel was the prize for rowing prowess. This was especially the case in Newcastle where the treacherous bar at the entrance to the harbour presented an additional hazard for the brave and skilful crews.

Competition between suppliers spurred the development of butcher boats which were 'light', strong, double ended, clinker built boats, between 24 and 30 feet long, about 5 feet wide and 20 inches deep. Although fitted with thwarts (seats) for four rowers and a coxswain, a crew of just two runners was common. They were normally pulled by four pairs of sculls but could be rowed with four oars. Working (as opposed to the racing model) butcher boats were often fitted with a mast to allow sailing.

Butcher boats were an improvement on the slower watermens boats that were designed more for use on harbours and rivers. To call them light is something of a misnomer as they were only light in comparison with other timber, clinker-built boats of the time. Of five butcher boats weighed for handicapping purposes prior to their use in a race for Water Brigades at the 1906 NAR, weights varied between 374 and 425 pounds (lbs) i.e., 170 - 193 kg. Two on the lighter end of the scale were new, especially built for racing. At these weights, it is fair to say that they are somewhat heavier than their modern equivalent fours and quads which weigh approximately 52 - 65 kilos.

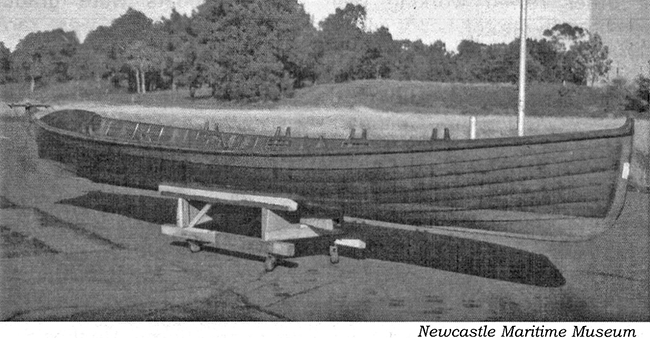

Butcher boat.(c1918). This one is 25'6" long, 5'4" wide amidships and 2' 21/2" deep.

Even though they were built for speed, for some unknown reason butcher boats were not widely used in Newcastle racing during the period 1870 - 1914. The first recorded appearance of butcher boats in competition in Newcastle was at the Stockton Regatta in 1874. They appeared at a few Newcastle Annual Regattas rowed as coxed four pair sculls between 1902 and 1910, once with crews of 'allcomers' others with crews representing regional Water Brigades [the NSW volunteer flood rescue organisation].

Crew in a race for Water Brigades in Butcher's Boats at the 1904 NAR

Like other rowed working craft, butcher boats were gradually supplanted by motor boats so subsequent appearances were rare. A butcher boat race was held at Morpeth in 1920s between the Ripley brothers and Maitland RC. In May of that year the butcher boat championship of NSW was held on the Clarence River. On another occasion, crews from Maitland, Newcastle and Hanwood Island (representing the Clarence River) competed over four miles for £600. The interesting feature of the event was the crews. The local crew included three members of the Searle family, the most illustrious name in rowing in the Northern Rivers. The Newcastle crew included Norman, Theo and Eldred Towns, a family of legendary reputation in Newcastle. There is no evidence of butcher boat racing in the Hunter beyond the 1920s.

Among the names of the old-time runners are Hickey, Hughes, Buhle, Limeburner, Jackson, Trevellan, Spruce, Chilvers, O'Brien, Campbell, Samuels, Menzies, Dunnett, McCracken and Beeson.

Newcastle Rowing Club's links with the city's ancestoral butcher boat roots were briefly re-established in 1997 when it re-enacted butcher boat racing on the harbour as part of Newcastle's Bicentenary celebrations. Anyone interested can view a Butcher Boat at the Newcastle Maritime Centre.

BOAT DEVELOPMENT

The heavy, clinker built craft utilised out of necessity in the early years of competitive rowing were OK as working boats but not really suitable for racing. Pressure for faster boats resulted in technical innovations in England and America that brought about most of the major changes in boat design that we are familiar with today. These were adopted and proven by professional rowers over a relatively short period during the mid-late 19th century before gradually being adopted by amateur rowing clubs.

Traditional clinker-built boats with their hull of thick planks were gradually replaced in racing by carve! construction (1840s) in which the timber skin of the boat was butt-jointed to provide a smooth outer skin that improved boat speed by reducing drag. Even so, clinker built boats continued to be used in racing until well .into the 1900s. Elimination of the external keel (1850s) improved a boat's underwater profile further increasing boat speed. Open ends in many of the early boats eights and fours were soon covered by canvas or other material.

In the 1870s, the introduction of the sliding seat permitted effective use of the legs resulting in a longer, significantly more powerful stroke. The benefits of the sliding seat are simply (sic) explained in the following extract from an 1873 article on the subject published in the prestigious medical journal, The Lancet.

Swivel rowlocks in the late 1870s enabled the length of the slide to be extended by 12" - 16". The addition of a fin improved steering. Even steering by foot from the stroke seat is not all that new. A rudder worked by means of a piece of wood screwed on to the foot stretcher connected by wires or lines to the rudder were used in some boats in the early 1880s.

Outriggers

Arguably the most significant advance occurred in Britain in the 1840s with the development of outriggers (wood at first, then metal). Outriggers permitted the placement of rowlock outside the gunwale of the boat thereby allowing boats to be much narrower and hence, faster. Boats fitted with outriggers appeared for the first time in Australia at the Balmain regatta in 1855. Their use in Newcastle, initially by professionals, was most likely in the early 1860s. An 18-ft long wager boat fitted with outriggers was built by Mr W Irvine of Scott Street in 1865. A fault - its 'extreme sharpness' - caused its builder to capsize twice in the harbour on his first outing.

Four oared racing boats fitted with outriggers became available in Australia in the 1870s (although it was not until 1898 that the NSWRA decreed that from January 1899 all four-oared races were to be rowed in out-rigged boats). At about 19-20 inches wide and weighing 82 lbs they were less than half the width and about half the weight of a string test gig. Yet the latter remained in wide use until the 1890s. Based on decisions made in regard to other classes of boat, it appears clubs tended to prefer the strength and stability of wider timber boats. Although NRC was keen to acquire newer, faster boats these were thought to be unsuitable for the strong winds and tides experienced on the harbour. A modified variation known as a Regulation Four came into use in the early 1900s. Its first appearance in Newcastle was in 1909 when Sydney University, Mercantile and Balmain rowing clubs raced at the NAR.

Rowlocks

Rowlocks (oarlocks in the US) attach oars to a boat and act as a fulcrum for the rowing stroke. Historically, rowlocks have been attached to the gunwale but in racing boats they came to be placed at the end of an outrigger. Over time, an infinite array of methods have been utilised to carry out this function. Some of the earliest large craft included closed-top oar ports. Oar ports with open tops are very old and were common in naval rowing boats. A small boat version of the carport was a strong top strake with a slot to retain the oar. String test gigs had a rowlock of this type. Wooden pegs or pins (tholes) fixed to the gunwales with a thong to hold the oar in place have been popular for centuries and used well into the 20th century even though more sophisticated rowlocks were available. A wide variety of metal (galvanised iron, wrought iron, bronze, aluminium), 'horned' or 'U' shaped shaped, fixed rowlocks have been produced since 1900. Although swivel rowlocks were invented in the early 1800s, they were not universally adopted even by rowing clubs until the early 1900s.

The Racing Shell

What had emerged by the end of the 1870/80s therefore, were lightweight "shells" (because their structure was internal and a smooth delicate egg-shell like skin was formed around it), very similar to today's boats that are long and sleek with outriggers, swivel rowlocks and sliding seats. Since then, improvements have been derived more through lighter materials, oar design, improved rowing techniques coupled with modern training and sophisticated coaching methods rather than basic boat design.

Today, all these innovations are taken for granted. But their adoption was often resisted even by some professionals who preferred what they were used to, such as a fixed rather than a sliding seat. Many persisted with fixed pin rowlocks into the early 1900s, even in international competition, although they were regularly defeated by rowers using swivel rowlocks. As late as 1883, the Town & Country Journal commented that "of late, pulling skiffs have been covered in forward. This is bad if allowed as it will alter the light skiff to wager boats".

Even though sleek fast racing shells with all the gee-whiz fittings we expect today were available to rowing clubs by the end of the 1870s, the qualities of their predecessors remained popular in some quarters for many years. The Hunter River Professional Sculling Club and Raymond Terrace were just two local clubs that during the 1920s brought new Towns built 22' long, fixed seat, in-rigged, clinker built cedar skiffs for use in competition.

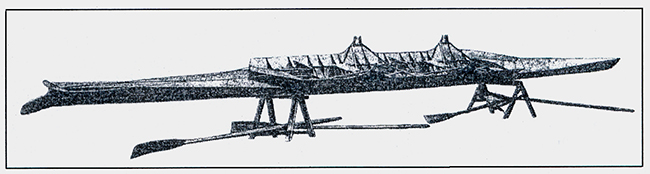

The evolution of racing sculls was characterised by sporadic adoption of new ideas. This is illustrated in the photo below of a double scull skiff used in competition by Sydney RC in the 1890s.

It is carve! built with the long low profile characteristic of the modern racing scull, is covered at both ends, has foot operated steering and sliding seats. On the other hand it is is inrigged despite outriggers having first appeared in Australia several decades earlier. The boat is wider than modern doubles but narrower that its inrigged predecessors. The poppet (rowlock) configuration is almost certainly in accordance with the "string test" classification.

To save anyone rushing to the boat shed with a tape measure to compare their boat(s) to the ones described above the following details might help. In Australian rowing, all boats must conform to a prescribed minimum weight ranging from 14 kg for a single scull to 96 kg for an eight. The only regulation on length relates to new eights which must be in two sections with no section longer than 11.9 metres.

The dimensions of modern racing boats vary but only to a small extent depending on the particular boat builder and the weight of the intended rower/crew. The approximate overall length of a modern boat is: single scull 7.6 - 8.3 m; coxed pair or double 10 - 10.4 m; coxed quad or four 13.65 m and eight 16 - 18m.

The quest for a new material, piece of equipment or some other development that will produce a faster boat is endless. Even when they do emerge they may not necessarily be adopted. Sliding riggers instead of sliding seats and a so-called 'drag reduction film' (1980s) are two examples. FISA, the body which governs international rowing, rejected both on the grounds that it would be unfair to poor countries who cannot afford decent boats as it is.

Details of early boats utilised for racing and the variety of shells that evolved to replace them are contained in Appendix A.

Oars

To be able to propel boats we need oars although one will do if it is done with a single oar from the stern - a la gondoliers.

Spruce (light and strong) and ash (heavy and strong) were regarded as the best material for wooden oars although other timbers such as oak, cedar, oregon, maple and pine have been used by some makers.

Up until the 19th century, oars came in a infinite variety of shapes and sizes so any discussion on the subject must be general in nature. The type of boat and how they were used influenced those variables. Typically they were about 12 ft long for pair oars to 13ft long for eight oars. Because they were easier to shape many of the early oars had square looms (shafts), however most oars were made from several pieces glued together (laminated) as they were stronger and less prone to warp. Oars made from a single piece of timber were less common being expensive, prone to warp and generated a large amount of waste during shaping. Sculls were between 10 ft and 10'4". By contrast, the average length of a modern sweep oar is 3.81 m (12'6") and sculls 2.98m (9'9").

Blades, like oars, have also undergone many changes in shape and width. Early competition oars sprung directly from general purpose ("pencil") oars which had long, straight and narrow blades barely 4" wide, with a square end. Subsequently, the search for more effective blades resulted in the coffin shape, (used around the end of the 18th century), the tulip shape 'macon' blade which was the preferred shape from around 1960 until 1991when the 'hatchet' or cleaver oar was introduced.

In the 18th century a curve was built into the blade that improved the oar's grip on the water at the catch.

Part 1 pages: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7

Previous < Introduction