History of Newcastle Rowing Club

Part 1 - Rowing in Colonial Australia

Part 1 pages: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7

Background

There is evidence of rowing races in classical Greece. Somewhat more recently, i.e. in the 18th century, watermen plying their trade on the River Thames in London were encouraged into impromptu races by passengers who bet on the outcome. Throughout the late 18th early 19th centuries these ad hoc matches evolved into organized racing contests between professionals whose skill and athleticism generated increasing public interest in rowing. Nonprofessional rowing was initiated by the upper class. Gentlemen took up recreational rowing thereby giving the sport respectability as well as setting an example that was enthusiastically followed by the broader population who took up rowing as amateurs, i.e. just for the love of it. That groundswell of interest led to the formation of amateur rowing clubs.

Racing on a regular basis is generally regarded as having started in London in 1716 when Thomas Doggett, an Irish playwright and poet established an annual regatta1 on the Thames for professional watermen. Boat racing in America was launched less than 50 years later in the waters around New York by professional ferry-and bargemen who, like their British counterparts, were urged to race by their passengers.

Early Rowing in Australia

The first rowing matches reported in Australia took place during the first decade after the first settlers landed. These were impromptu contests between sailors from visiting sailing ships using small craft ordinarily carried by their ships such as gigs, lifeboats, pinnacles, cutters, etc. As the colony developed around its ports and rivers, boatmen became essential to meeting the transport and service needs of the growing colony. Like their English predecessors, these professional watermen raced in boats they used on a daily basis - usually skiffs or gigs.

Most of these boats were built to carry goods and passengers plus as many rowers as necessary to propel them. They were not built to any particular standard or designed for racing. Although different builders built boats suitable for their intended use and the waterway on which they were to be used, it was natural that boats commonly used by watermen for the same purpose tended to be similar in construction and dimensions so they tended to fit within a certain class.

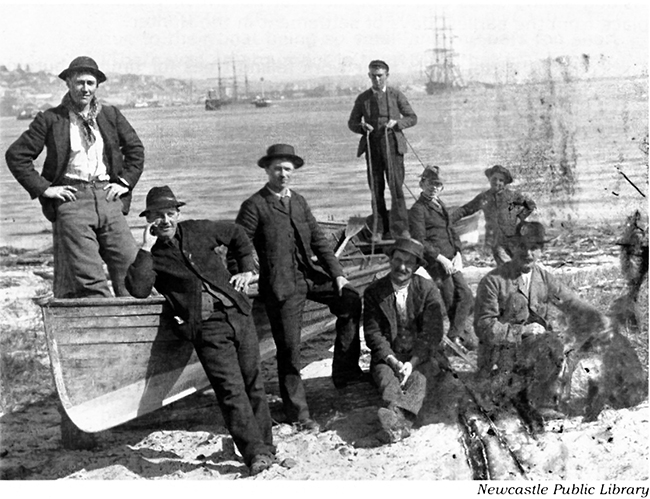

Light watermens skiffs like those seen here in the Market Wharf were a particularly popular boat in early racing. They were used with a pair of sculls, two pair sculls or two oars.

Four-oared gigs at the 1899 Newcastle Annual Regatta. Such boat were commonly used in local regattas because of their ready availability.

All these early boats were of traditional clinker construction (overlapping planks [or streaks] - rather like weatherboards). They were constructed with an exterior keel, square transom (stern), fixed seats and yoke and rudder steering. Fixed seats required a rowing stroke that involved a fairly simple movement using the upper body. Legs remained static adding nothing to the stroke. Sheer power was required with skill a secondary consideration.

Oars rested on the side of the boat held in place by a thowle (two fixed vertical pins - sometimes called a poppet head). A thong was used to tie the oar down otherwise they tended to jump out. Boats with poppet heads or rowlocks fitted to the gunwale of the boat were referred to as being 'in-rigged'.

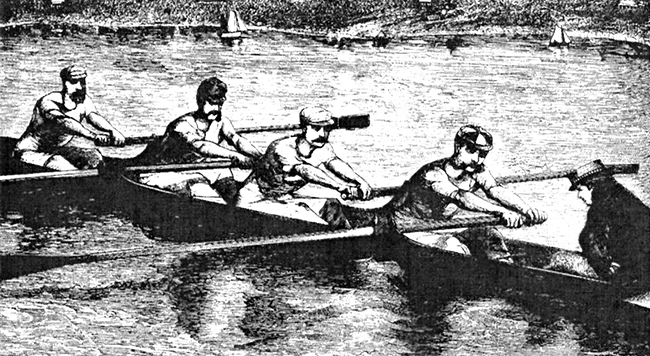

The NSW (in reality, Sydney) four in training for the 1874 intercolonial amateur regatta demonstrating the upper body action used in fixed seat boats.

Boat races in the early 1800s were common but, as indicated, they were predominately between seamen and/or between professional watermen rather than as part of organised aquatic carnivals.

It was the organisation by local committees of multi-event regatta carnivals throughout the individual colonies (states) commencing with Hobart in 1827 that opened opportunities for others in the community such as amateurs and juniors, not just professional watermen, to participate in rowing races.

As will be seen, local regattas catered very well for a wide range of people who could already row, however they provided no avenue for novices to enter the sport.

In Australia, as in Britain and America beforehand, the formation of amateur rowing clubs opened the way for this band of new enthusiasts to row. Clubs also expanded the opportunity for more frequent rowing and regular competition rather than being restricted to the occasional local regatta, most of which were held annually.

Melbourne University Boat Club, Australia's first, was founded in 1859. In Sydney, the Subscription Rowing Club (1859) was renamed Sydney Rowing Club in 1870. Newcastle Rowing Club was formed in late 1870. These were the forerunners of the numerous rowing clubs and institutions spread throughout the country that maintain Australia's status in the international sport we are familiar with today.

Throughout the latter half of the 19th century competitive rowing flourished in Australia attracting an enormous following with tens of thousands attending major professional contests and regattas. Reasons for such enormous public interest included the sport's prominence due to a succession of Australians world champions, limited alternative entertainments and a festive atmosphere. Betting on races was also a major attraction.

Press coverage undoubtedly played a major role. All aspects of rowing such as challenges, events, results and related activities were extensively reported in the press. Newcastle was no exception. Newspapers such as the Newcastle Chronicle, the Miners Advocate, the Newcastle Pilot, the Newcastle Morning Herald and, the sort-oflocal, Maitland Mercury regularly reported on club activities as well as regional, colonial (State), national and international (predominantly British and American) rowing news. Coverage extended to detailed discussion of forthcoming club races, even if they merely involved a mid-week race between two boats. A report of such races invariably followed a day or two later. Club social activities such as balls, concerts and picnics were similarly reported in fine, not to mention eloquent, detail.

There is a persuasive argument that prior to and immediately after nationhood in 1901, rowing contributed substantially to Australia's national identity. When Edward Trickett won the world sculling championship in 1876 he became Australia's first world champion in any sport. He was followed by New South Welshmen William Beach, Peter Kemp, Henry Searle, James Stanbury, John McLean and George Towns. Collectively, they held the title for 22 of the following 32 years. This success, most often against Britain's best rowers, helped to convince Australians of their worth, instilling a sense of pride that they were in no way inferior to the best the Mother Country had to offer.

Early Rowing in the Hunter Region

Fittingly, European discovery of the present site of Newcastle was by rowers manning a five-oared whaleboat. [Five oared? How can that be? We all know that there must be the same number of oars each side of a boat otherwise it tends to go in circles. An explanation, of sorts, can be found elsewhere; try Appendix A.]

On 9 September 1797, Lieutenant Shortland, an officer of the Royal Navy, and his crew were travelling up the coast from Sydney in search of escaped convicts when they chanced upon a harbour and a very fine river. This, Shortland named after Governor Hunter. Like hundreds, perhaps thousands, of rowers since, he rowed some distance up the river and to the northern (Stockton) shore. Shortland's whaleboat was most appropriate. Whaleboats were designed for speed in the chase whereas the majority of boats in use at the time were built to carry goods and passengers.

Following early settlement, Newcastle Harbour and the local river system were of vital importance to regional commerce, industry and general transport. The scattered nature of settlement and poor or non-existent roads meant that people rowed for a livelihood: delivering goods, produce and services by boat. Licensed professional watermen (who were licensed by the Marine Board, based on testimonials to their character and experience) provided a form of aquatic taxi service around the harbour and rivers and between the shore and ships moored in the harbour.

Newcastle Watermen

Many people used boats as a normal method of every-day transport and it was common for schoolchildren to row miles to and from school each day. Occasionally, even funeral corteges were conducted by boat. For many, rowing was a pleasure. For others it was also a sport with the chance to win a trophy or prize money - a lot for a few of the very top professionals -and occasionally, a championship title.

The Beginning of Boat Racing in the Hunter

The early history of rowing in and around Newcastle survives only in what was recorded in the newspapers of the day. The Maitland Mercury started in 1841, the Newcastle Chronicle (later the Newcastle Herald and Miners Advocate) started in 1859. Consequently, any record of boat racing on Newcastle Harbour between permanent settlement in 1804 and the first newspaper in 1841 went unreported. Reliance on the Mercury meant that between 1841 and 1859 coverage of happenings in Newcastle was patchy. Subsequently, it was dependent on activities being reported in the Chronicle. Obviously, the absence of newspaper items on rowing matches or regattas does not necessarily mean that none took place.

No record remains of the first boat races in Newcastle. Nevertheless, based on what occurred at ports and rivers elsewhere in Australia we can be confident that impromptu contests between the crews of visiting sailing ships and amongst local watermen would have taken place from the earliest days of settlement in the Hunter.

The convicts, absorbed in their work felling trees for timber, burning shells for lime and breaking big rocks into little ones, had little time for recreational pursuits.

Given the inevitability of impromptu match races within Newcastle's strong maritime culture, it is not surprising that the next step - organized races - followed. Suggestions by some sources long afterwards that a maritime festival took place on the harbour in either 1834 or 1835 and a regatta in 1840 can be neither discounted nor confirmed.

The first regatta in the region on record was held on the Hunter River at Maitland on Monday 21 October 1844. Four events were contested over courses of varying lengths down the Maitland side of the river towards Wallis Creek, around a turning buoy, back up the river on the opposite side, around another buoy then to the finish line opposite Hunter Street where the steamer 'Huntress' was moored.

Intriguingly, the course for the 4th race was only decided by stewards after the third race. It may have depended upon which boats the entrants selected.

Race 1

10.00 am. Boats pulling 4 oars. First prize £62; second £2. Entrance 6/-. John Hannell's crew rowing with strength and "beautiful precision" in 'Peri' (white flag, red ball) won by 400 yards from Captain Patterson in 'Lucy Long' (blue ribbon') with Mr Johnson I 'Flycatcher' (light blue & white stripe) 450 yards further back in third. The fact that the 'Peri' was the swiftest boat with best oars emphasized a common problem for regatta committees of the time - the need to ensure racing was between well matched boats with a reasonable set of oars.

Race 2

12.00 md. Boats pulling 2 oars. First prize £4; second £1.5s. Entrance 4/-. After a restart, Captain Pattison's 'Jim-along-Josey' (blue ribbon) won by 300 yards from Mr Belcher's 'Margaret' (sky blue & green flag) with Mr Johnson's 'Eclipse' (blue & white), 100 yards further back. Hannell's 'Trail' (white & red ball) withdrew before the restart but rowed the course anyway. Boat equality was again an issue as it was subsequently argued that the 'Margaret' crew should have been given the race due to their boat being so small and the oars too short. [There was an argument in the 1870s that any action to standardise boats would be detrimental to competitive rowing as it would discourage innovative boat building. As will be seen, there were spectacular advances in boat design during this period].

Race 3

2.00 pm. Boats pulling a pair of sculls. First prize £3; second fl. Entrance 3/-. Mr Hannell's 'The Sweep' (white & red) won what was a row-over. Mr Yoeman's 'Brock' only entered to qualify for the Ladies Purse but then didn't race.

Race 4

Ladies Purse. This is not a race for ladies, as the term 'Ladies Purse' also appears in other sports such as horse racing. It was, in fact, a purse containing prize money collected by ladies who supported rowing. Typically, the purse was elegantly worked with the addition of ornamental beads, silks, etc., by the ladies who donated it. Occasionally the amount of prize money was not revealed until the winner actually opened the prize after the race. In this instance the winner's purse contained £3. 10.0. Second place purse held £1.10.0. Entry was open to any boat that participated in any of the preceding three events. Contrary to what might be expected, the three entrants selected pairs rather than fours. Hannell's 'Trail' won by 400 yards from Mr Johnson's 'Eclipse' that was pulled hard but was disadvantaged by weak, badly matched oars. Belcher's 'Margaret' which was third suffered from a similar problem, its good set of oars having been removed after an earlier race. Their shorter replacements meant that the crew was not competitive.

Events were scheduled at 2-hour intervals from 10.00 am. Races during that era took about 18 - 25 minutes so, for spectators, the action was hardly continuous. Nor, given the winning margins, would the racing have been particularly exciting. Even so, the organizers expressed satisfaction with the success of this their first regatta.

The first regatta recorded in the port of Newcastle was held on 3 April 1845 during Easter. It was a modest program with just a sailing race and one for boats pulling four oars with each boat steered by its owner. The prize for the latter was a silver cup. Mr Bolton's boat won an excellent match defeating boats owned by A W Scott and Mr Richardson. One belonging to the steam dredge - a link that inevitably conjures an image of a plodding work boat -was last.

Regattas in Newcastle and Surrounding Areas

The regatta idea caught on. Over the next few decades, enthusiasm within other communities for their own regatta meant that they came to be held more widely throughout the region.

Several of the earliest were Hexham (1849), Raymond Terrace (1854 ), Stockton (1862), West Maitland (1862) and Wallsend - Plattsburg (1878). Stockton and Wallsend - Plattsburg were two of the most durable, both lasting until well into the 20th century. There were many smaller, less frequent regattas with shorter time spans held throughout the district. Maitland and Morpeth were held occasionally while others such as Speers Point, Tomago, Hexham, Belmont, Mayfield West, Toronto, Galgaba (Pelican Flat), Raymond Terrace, Hinton, Nelsons Bay, Port Stephens (at Mungo Brush) and Mosquito Island were held even less often, in some instances, just once or twice. None of these however gained the importance or matched the longevity of the Newcastle Annual Regatta (hereafter referred to as the NAR).

Apart from New Years day, public holidays such Anniversary Day (Australia Day - 26 January), Prince of Wales Birthday (9 November) and Easter were popular for regattas. Other holidays such as Boxing Day, Queens Birthday (24 May) and St Patrick's Day (17 March) were used occasionally. It is testimony to the popularity of rowing in the Hunter that on at least one occasion (9 November 1893) three regattas were held in the region on the same day (Stockton, Belmont and Morpeth), all of which were attended by large crowds.

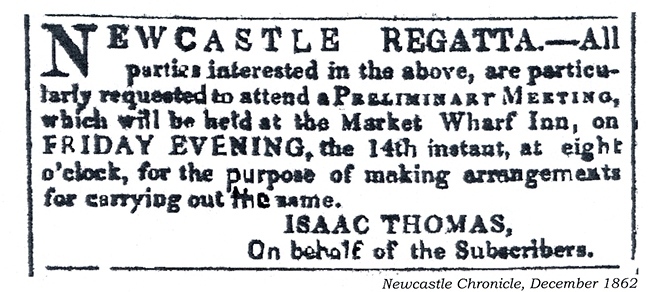

Organisation of regattas in and around Newcastle was the same as in other localities such as Sydney and the Northern Rivers. In a system that lasted until well into the 1900s, rowing enthusiasts within a community called a public meeting to gauge the level of interest. If that was high enough a committee was formed to plan and run that single event only.

Once the regatta finished, prizes awarded and accounts finalised, the committee disbanded until possibly the next year. A successful regatta generally ensured that a year or so later a new meeting was called, usually by a member of the previous year's committee or a representative of the subscribers, and the process was repeated. Thus it was that aquatic regattas began a tradition in towns and cities across the country.

Such advertisements were the first step towards holding local regattas - in this case the 1863 Newcastle Regatta.

A local regatta committee could consist of upwards of 20 people. But who were they? In many cases the same names keep cropping up in sports (such as rowing, rugby, horse racing, cricket and yachting), charities, school and hospital boards and as patrons of the arts. In the main, those involved not only ran their own business but were directors in other companies so had extensive links within the business community. Obviously they socialised within that circle. This is exemplified by Joseph Wood, a businessman and a long-time president of NRC in the late 19th century, who married the sister of Clarence Hannell, another businessman who was also involved with rowing clubs and NARs. It seems likely that people within such local networks coaxed individuals they associated with into joining various community and sporting organizations. These connections would probably reinforce an already strong sense of obligation and public spiritedness derived from their social position. Lack of any previous experience in a sport was no impediment to involvement with business contacts and acumen seen as being more useful.

The concept of independent committees organizing regattas that catered for their own community without answering to any outside authority might appear attractive. In fact, by 1881, anomalies between the numerous independent regatta committees were causing problems. No one regatta recognized any other. Disputes over what constituted a junior, senior or novice were common. Differentiation between amateurs and professionals was important yet the status of many rowers was unclear with each regatta adopting its own rules of racing. With no central organization, these issues were not able to be resolved by local committees except to the extent that these tended to copy what happened in Sydney, although, there too, there were variations. (By contrast, the relatively new amateur rowing associations responded to the need for uniformity by introducing general rules (applicable only to their affiliated clubs) in relation to racing, boat specifications, and differentiation between amateurs and professionals. As will be seen, regulation of the latter issue only added complications.

Local regattas consisted of between 4 and 15 events, about threequarters of which were rowing or sculling races; the remainder were for sailing boats. With races held at 30 minute intervals, fifteen events was about as many as could be held in the time available based on an 11 o'clock start and a break to allow the officials to indulge in luncheon and the inevitable speeches. The program for the 1878 NAR is indicative of the variety of events conducted at the time.

Race 1

For youths not exceeding 19 years old pulling two pairs sculls with cox in working licensed watermens boats. Row a course around the harbour marked by buoys. First prize £6; second £1.10s.

Race 2

Working licensed watermans boats under canvas. Sail around a buoy at Port Waratah. First prize £7; second £2.

Race 3

For gentleman amateurs who do not earn their living by manual labour employed in public and private establishments. For two pair sculls with cox in working licensed watermens boats that have been worked in Newcastle one month prior to the regatta. First prize, trophy.

Race 4

Fishermen in fishing boats employed in fishing on the Hunter River with 4 oars and cox manned by men regularly employed as fishermen on the Hunter River. First prize £10; second £2.

Race 5

Dinghies not more than 18' 6" long under canvas. Handicap.

Race 6

For all comers. A pair of sculls in working licensed watermens boats. First prize £10; second £2. Handicaps applied to the three entries were 70 lbs for one and feather [i.e. nothing] for the other two.

Race 7

For amateurs. Four pair sculls with cox in boats not more than 28 ft overall. First prize £10; second £2s.

Race 8

For amateurs who have never won a prize. A pair of sculls in licensed watermens boats. First prize £6; second £1.

Race 9

Boats not more than 28 feet long under canvas.

Race 10

For amateurs working on cranes or railways, a pair of oars with cox in working licensed watermens boats. First prize £8; second £2.

Race 11

For allcomers. Two pairs of sculls with coxswains in working licensed watermens boats. First prize £8; second £2.

Race 12

Gig and dinghy race.

As might be gathered from the above, boats used prior to the advent of racing sculls were dingheys (usually for youths), light skiffs for singles, doubles and pairs and larger boats or gigs for both four pair sculls (quads) and four oars. These and other boats used in racing are described in Appendix A.

Local regattas almost always conducted one or two rowing races that catered for work-related or special interest groups within the community. Newcastle examples included settlers, gentlemen, local residents, miners, sanitary workers, defence force personnel, crews from visiting ships (in ships boats), shop assistants, professional people, farmers, fishermen/prawners/oystermen, firemen, trade unionists, people connected with the milk trade, navy personnel, lifeboatmen, life-boat rocket brigade, ladies, boys (under 15 or 16 or 19), shipwrights, lime-burners, railway and tramway employees, flood boat crews, watermen, ballast-men/coal trimmers/lightermen, straith [wharf] workers, coal and railway crane employees, men employed in the government service and duffers. [Since the last-mentioned is unlikely to refer to cattle thieves, presumably it means anyone incompetent or clumsy when it came to rowing.] Some races were restricted to employees of a particular business. Novice events were common. Gradually, from about 1870, local regattas began including one or two races for rowing clubs.

Ample racing was provided for professionals at local regattas with several events specifically allocated to watermen or those involved in work that classified them as professionals. In addition, "all comers" races, because of the prize money involved, were automatically limited to professionals or people who weren't particularly fussed about retaining an amateur status. Professional match races were not conducted at these local regattas.

Some interesting features of the Morpeth - Hinton Regatta in 1845 are worthy of mention. It was run over two days, 20 & 21 October, with four races held on each day. Inevitably, the long delay between races resulted in a dull event. The program included a race for "aboriginal natives" in aboriginal canoes for a prize of a suit of slops [i.e. cheap, ready made clothing] for the winning pair. It did not eventuate as only one canoe could be found. One unusual innovation was a requirement that 5% of prize money was to be donated to Maitland Hospital. Another was that starts and finishes alternated between the two host townships. Since these townships were about 2. 5 km apart it is no surprise that the concept was not a success.

At the Hinton Regatta in June 1883 there was a forerunner of veterans or masters' events that were to become commonplace a century later - "all comers over 60 years old". It was a handicapped event for single sculls in farmer's working boats over one mile. Of the "game old scullers" Hinton was supposed to possess, three entered. Raymond Terrace Regatta in December 1891 included a similar event for comparative youngsters; "all comers not less than 50 years old".

Novelty Events

A novelty event was included as the finale for most regattas of the time. Of these, a gig and dinghy race or, more accurately, chase was the most popular and amusing. They involved four rowers in a gig having to chase, and the bow man catch, a lone rower in a dinghy within a 15 minute time limit. This sounds easier than it probably was. The dinghy rower had to evade capture as best he could. A smaller, more manoeuvrable boat helped. Rowing around boats spectator craft or diving overboard and swimming for it (in which case the gig's bow man had to follow) were the usual tactics. If possible, the dinghy rower would try to clamber into the gig while its bow man was still in the water. This gave him some respite and embarrassed the gig crew. A spectacular technique employed by the chasers was for the bowman to take a flying leap into the dinghy. This occurred at one such event in Newcastle in the mid 1870s. Following a successful jump, the gig bow man got hold of one leg of his flailing quarry who, in his attempt to break free, was half in/half out of the boat, face down in the water. It is not known if his escape was due to wild kicking or compassion on the part of his chaser unwilling to cause a drowning. Capsizing the dinghy, then swimming after its rower was within the rules. It wasn't prohibited anyway. At one such event at Maitland in 1863, the dinghy rower, with 5 minutes to go, made for the shore, was chased among the spectators by the gig man before returning to his boat and rowing around the flagship. His efforts were enough to evade capture within the time limit but he was disqualified anyway under a rule requiring that he stay within prescribed boundaries. One consolation for the wasted effort may have been the newspaper report that expressed admiration for the rower's determination and regret for his disqualification.

Examples of other novelty events were races for punts; rowers dressed in costume and boats in which the rowers and a sweep all used short handled shovels.

At a small, unseasonal regatta in August 1896 each contestant was in a pram pulled, naturally enough, by a pair of oars. The Stockton Regatta in 1885 included a "hurry-scurry11 race; a go-as-you-please format for boats using oars or sails or both. One of the three entrants carried five pair of sculls, the others four pairs of sculls. "Jumbo11, one of the latter, won (Surprise! Surprise!) by making best use of its sails. Belmont Regatta held a similar event in 1888.

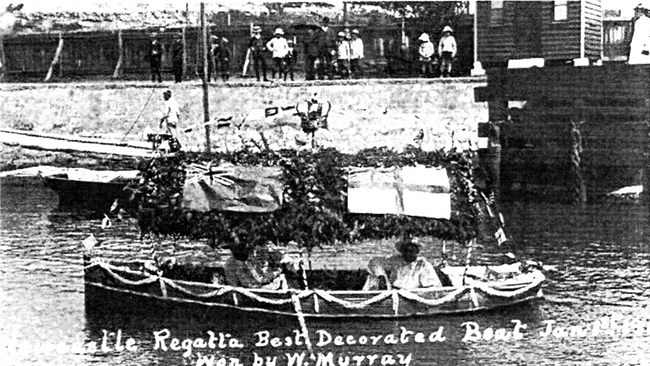

Occasionally, there would be a decorated boat competition.

Open to boats with a beam [width] of 7 ft and over, it gives some idea of the size of boats used at times. Obviously anxious to be innovative and offer patrons something new, organisers of the 1882 Stockton Regatta introduced what was called a Sea Horse race. Unheard of beforehand, it was a mystery to entrants (lured by the 10/- prize money) who, like everyone else present, had no idea of what it was all about. The outcome was a confused shambles that may explain why the event was never heard of again.

One-man tubs sculled by a single oar on the stern competing at a NAR in the early 1900s.

For a long time, races involving rowers, each in a tub using one paddle, were very popular. Occasionally, NARs featured washing tubs, other times bath tubs. Distance paddled was short and probably immaterial anyway. The imperative of merely staying upright surpassed progress - certainly for the washing tub anyway.

Duck chases were held occasionally involving boats with a two-man crew. It was the bowman's job to catch the duck. One such event conducted at the Morpeth regatta in 1886 was referred to as the 'catching duck on water". Presumably, the ducks involved had their wings clipped to prevent flight - as opposed to fleeing. This type of event presented several hurdles for the organisers. First, the poorer quality duck employed invariably displayed a selfish sense of self-preservation by attempting to avoid capture (with their ultimate fate in a cooking pot).

Another type of single-oared tub. Built along classical lines, they display all the grace and speed typical of their class.

Even worse, their total disdain for a regatta timetable was evident to all at the Wickham regatta in 1905 when the duck eluded capture for 45 minutes. Going on the experience at a Hunters Hill regatta in 1860 where geese were used instead of ducks, such events weren't always fun. Probably not for the geese/ducks either. On this occasion, spectators in boats interfered, herding the birds towards their pursuers. A resulting suggestion was that, next time, spectators be prohibited from whacking birds with an oar. Furthermore, and proving once again that poor planning will always let you down, the geese collected were tame so not inclined to enter into the spirit of the chase. Apparently they are supposed to be wild. Given their treatment, you'd think they'd be furious.

An event that fits within the novelty category was held at the Hunters Hill regatta in the 1859 and may be of interest to readers even though such an event was not held at any regatta in Newcastle and, perhaps understandably, does not appear to have been replicated elsewhere. Called a tournament, it entailed bouts between two boats, each with two rowers and a cox plus a man on the bow wielding a padded lance. This was used to upset his opponent. One wonders how some of the above events would survive on a program these days especially in relation to duty of care and insurance coverage when there is a distinct likelihood of death or injury.

Vaguely within this context, the following occurred in France in 1917. It didn't involve NRC members. It may have involved Australians but even if it didn't it's a good yarn anyway. A battalion removed from the front for rest and recreation, sought approval of its divisional headquarters to hold an athletics carnival. All events were approved except for the proposed 'boat race'. "Most dangerous" said HQ: men might be drowned. A humble letter went back next day explaining that it was a dry boat race involving groups of eight men carrying a log over an obstacle course. The resultant decision was that, "as the boat race is not aquatic and you undertake to see that no water is used before, during or after the race to float the logs, the race will be permitted". It is comforting to learn that amid the carnage of the Western Front when soldiers died in their thousands each day, the military hierarchy took such pains to ensure that its troops suffered no injury during authorised sporting activities.

Given the obvious dangers inherent in those "novelty" events as well as the normal accidents that can occur in boat racing, particularly during the congestion as crews jostled for position when rounding marker buoys, it is not surprising that regatta reports often finished with the comment, expressed with obvious relief, that no serious accidents occurred. One example is the report of 1866 NAR which mentioned that there were "a few accidents resulting however in no loss of life or limb". One of the accidents was when a lighter [a type of work boat] completely smashed a skiff. The cox and two rowers escaped with no damage but a dunking.

Rowing Courses

At the risk of stating the bleedin' obvious, courses depended on the waterway. River courses were often called 'straight' even though they contained bends. Many river regattas used out and back, once or twice around courses for the benefit of spectators.

In the open waters of Newcastle Harbour, courses set were of varying configurations and distances. NARs were held around a triangular or rectangular course marked by buoys or moored boats in an area roughly between the pilot station and the end of the Dyke. Contestants rowed once or twice around, starting and finishing at the flagship. The benefit of that layout was that spectators on the shore could view the start and finish and at least some of the legs. This was not possible at straight courses over the long distances then rowed, usually in the order of 3 miles (5 km) or more. On the Stockton side courses were usually parallel to the shoreline -either one way or, out, around a buoy and back.

The Hunter River at Raymond Terrace was the favourite local course for match racing and championship deciders as it allowed racing over the normal championship distance of 3 - 31 /J miles (as was the Parramatta River course). A race in light skiffs over that distance took about 22-24 minutes. Races were also held there over shorter distances, sometimes with the use of a turning buoy near the confluence with the Williams River. The Hexham River course started about 700 yards north of the Travellers Rest Hotel east to a buoy moored near lronbark Creek.

Apart from the desirability of steering a straight course, the need to safely and effectively negotiate turning buoys may also have been a reason coxswains were retained for decades in most boats.

Public access to racing was rarely easy. The Raymond Terrace course for instance was midway between the major population centres of Maitland and Newcastle. Travel from Newcastle was either by carriage which was a long trip at the time, particularly as there was no bridge at Hexham, or by steamboat which took two hours with the tide or two and a half against it. The steamboat fare in 1891 was 5/- return. Other venues presented similar transport problems. For a small four event regatta at Toronto in 1890, two special trains were added to the normal service to take spectators to Cockle Creek where they caught a steamer to Toronto. Four steamers plied between Cockle Creek, Toronto and Belmont. [Toronto, incidentally, was named in honour of the birthplace of the champion Canadian sculler Edward Hanlon who was visiting NSW when that area of Lake Macquarie was being developed].

Financial Aspects

Money to cover costs was raised by selling or auctioning catering rights.

Businesses competed for the opportunity to cater on the flagship: operate publican booths and refreshment stalls (cake, fruit, etc) on the wharf: to print race programs and to provide a venue, such as a hotel, where prizes were awarded after the event. For example, the 1873 NAR committee sold these rights for more than £60. A publicans booth on the flagship went to Mr Eiles for £10.0.0: a cake & fruit stall on the flagship (Walter Hudson) £1.1.6 and rights of admission to the flagship (Mr Hudson) £30. On shore, the No 1 publicans booth in the goods shed went for £7.2.6 (Mr Fieldhouse): No 2 in the goods shed £5.0.0: the goods shed cake & fruit stall (Mr McLardy) £1.5.0: No 1 fruit & cake stall (Mr Forbes) £2.0.0: No 3 fruit & cake stall (Mr Mackenzie) fl. 1.0: No 4 (Mr Hudson) £1. 7 .0: toy booth, (Mr Hudson) £1.0.0: right to print programs etc. (Mr Hudson) 12/6. Publican booths Nos 3 & 4 were to be disposed of privately by the secretary. Frank Gardiner, as Honorary Secretary of the NAR for many years, was responsible for distributing these rights. As a professional auctioneer he conducted these auctions personally yet, interestingly, there was never any questions raised about possible conflict of interest. The amount raised might be compared to £193 raised by Sydney Anniversary Regatta committee in 1874.

The general public was charged for entry to the flagship where they could dance to the music of a live band (a pleasure presumably limited to larger flagships), eat, drink and mingle with the dignitaries.

Some regatta committees encouraged people to become subscribers entitling them to reduced entry fees for the race and the flagship. For example, the entry fee at the 1863 Stockton regatta for rowers who were non-subscribers was 8/- per £ of first prize money or trophy value. Subscribers paid only 2/- per £. Where entry fees were required this could have been either:

- a specified amount for each event ranging from a few shillings to several pounds depending on the status of the regatta, the nature of the particular race and the prize/prize money offered, or

- a set proportion of the first place prize money. This varied for different regattas, was usually either 5 or 7.5%, but went as high as 10%. A fee might also have been charged for the hire of boats used. A hire fee for a crew boat at a regatta in 1897 was 1/6.

At one regatta (Raymond Terrace, 1859), no boats were allowed unless the owners subscribed 5/-. Such a charge does not appear to have been applied elsewhere. One has to think that it would not have been in the best interests of the organisers as it would only discouraged owners from making their boats available.

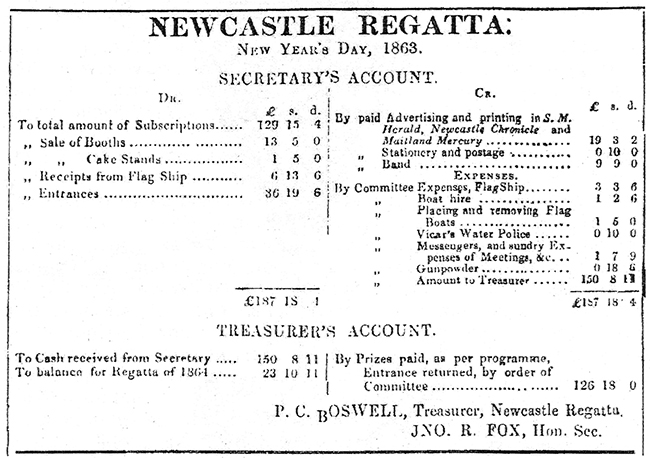

An example of the sources of income and costs of running a regatta in Colonial days is shown below in a summary of a financial statement for the 1863 NAR.

For those who are wondering, the gunpowder was used in a cannon for a 10-minute warning gun and the race start. As the cannon was audible up to three miles away, rowers were left in no doubt that they should commence racing.

In comparison, income for the much smaller 9-event Wallsend-Platsburg Anniversary Day Regatta in 1890, was derived from the sale of booths (£22), publican booths Nos 1 & 2 (£8) and refreshment booth (30/-).

Prizes

Prizes were usually awarded for first and second place. Professionals and manual labourer amateurs won prize-money while bone fide amateurs received trophies. Trophies were often donated by individuals, particularly wealthy rowing supporters, as well as by local businesses. They covered a wide range of items from the traditional silver cups and goblets to items of apparel, sculls and other more practical items for everyday use.

A prize awarded at the Stockton regatta in 1862 was a "pretty" pair of silver sculls 10" long. For the 1874 NAR the prize for youths pulling two pair of sculls was a donated silver cup. Valued at £6.6s, it was 6" high, enriched with a design of frosted silver and with two oval tablets for the inscriptions. Another prize was a handsome claret jug. Made of sterling silver it was 12" high and 5" wide across the bowl. The design was a series of wreaths of roses in burnished and frosted silver round and surmounting the bowl on which there were two tablets: one for the inscription and one for the name of the winner. Trophies or prizes for the 1891 Newcastle Annual Regatta for instance included a silver cup valued at £15.15.0: a marble clock at £12.12.0: a silver tankard and two cups at £10.10.0: a silver cup at £5.5.0 and a cask also £5.0.0. As one would gather, these are valuable and handsome prizes. How valuable? Well, £1 in 1891 would, roughly, buy the same as $57 today.

The above photograph gives some indication of the quality of prizes awarded at small local regattas. It is the first place trophy for a race at the Stockton Regatta in1882. Open to residents of Stockton pulling two pair of sculls in working watermens skiffs, it was a standard race for regattas at the time, so nothing special. Yet, this is a fine silver cup decorated with a garland of what appears to be white lilies around the body of the vessel and with two decorative "ring" type handles. The cup is mounted on a decorated base and supported by three oars. It is inscribed with the name of the winners and the date. Its value is unknown.

The practice of publicly displaying prizes intended for forthcoming regattas provides further evidence of the public interest in rowing. For example, in December 1873, trophies for the upcoming 1874 Newcastle Annual regatta, all of which were of sterling silver, were displayed in C Provost's jewellers shop in Hunter Street. The prize for youths double scull race was a 6 inch high silver cup valued at 6 guineas presented by Captain Stafford of the barque "Camille". Mr Hannell presented a handsome claret jug worth about 12 guineas. Twelve inches high, the design was a series of wreaths of roses in burnished and frosted silver around and surmounting a 6" wide bowl upon which were two tablets for inscribing the event and the winner's name. In a race for amateurs, two 7 inch high, sterling silver claret cups were much sought-after prizes.

The Newcastle Annual Regatta (NAR)

Following that first tentative experience on Newcastle harbour in 1845 it was widely agreed that as the second city in NSW and an important economic centre, Newcastle should hold a regular aquatic regatta along the lines of Sydney's Anniversary Regatta.

The regatta was repeated on New Years Day 1847 though on a larger scale with six events - two for sailing boats; four for rowed boats. The race in whale boats was won 'cleverly' by James Hannell's boat defeating the pilot's and Mr Fisher's boats. 'Spitfire' defeated Mr Bolton's boat in a well-contested race in gigs. Mr Stacy won the dinghy race. John Hannell won the sixth race beating a 'strange boat'. We will never know what that intriguing term entails. The day was a great success with two items of interest. First, one of the sailing boats capsized and sank and may still be at the bottom of the harbour today. Certainly, it hadn't been recovered at the time of the newspaper report three days later. Secondly, the reporter opined that it had been the best regatta he had witnessed in Newcastle Harbour - a strong indication that there had been others previously. It is to be hoped additional information will emerge that will tell us more about early rowing in Newcastle.

Like many others around the country, the NAR took some time to find its niche and develop an organisational framework. The 1845 and 1847 regattas, and possibly others unreported, are probably best regarded as the first tentative steps towards a regular regatta in Newcastle. Who could have envisaged then that these small beginning would, by the mid 1860's, have become the enormously popular Newcastle Annual Regatta, a regionally significant social and sporting occasion that would last for over half a century?

A regatta on the Queens Birthday, Tuesday 26 May 1857, could reasonably be considered the first. Thereafter, regattas on the harbour were held most years until 1914 then reactivated, briefly, in 1920 and 1921. The 1857 program was relatively small with just seven events with a format based on earlier established regattas such as Balmain and Sydney. All races were for prize money of up to £10. Entrance fees varied between fl and £1.4.0. James Hannell was President, Treasurer and Starter.

In 1861, the Newcastle Regatta was conducted on Anniversary Day (26 January). Seven events were conducted including three for sailing boats, one for whale boats pulling five oars, two other rowing races plus what was the finale at most NSW regattas - a gig and dinghy race. By 1863, the program had grown to 10 events.

Clarence Hannell commenced his long association with the regatta joining his father on the Committee as the Hon Secretary. A notable addition to the committee as Vice President was E C Merewether who, in 1870, would become the first President of Newcastle Rowing Club.

Whilst the concept of an annual regatta was gaining popularity the sporadic timing suggests that there was some uncertainty about an optimum date. From 1863, NARs were held on New Year's Day. This decision was, almost certainly, based upon earlier experiences when it was found that other possible dates such as Easter (April) or the Queen's Birthday (late May) were too short or cold or susceptible to strong winds, conditions that are neither conducive to good rowing nor comfortable for spectators. In addition, the committee would have been anxious to avoid any clash with the Anniversary Regattas in Sydney. This decision led to the NAR becoming one of the largest and best-known sporting events in NSW, equalling and often surpassing the popularity of Sydney's Anniversary Regatta. In fact, the latter were often unsuccessful, failing to attract either a disinterested Sydney public or local rowers. By the mid 1860s, an experienced committee had been formed in Newcastle, full racing programs were being conducted and public acceptance was growing.

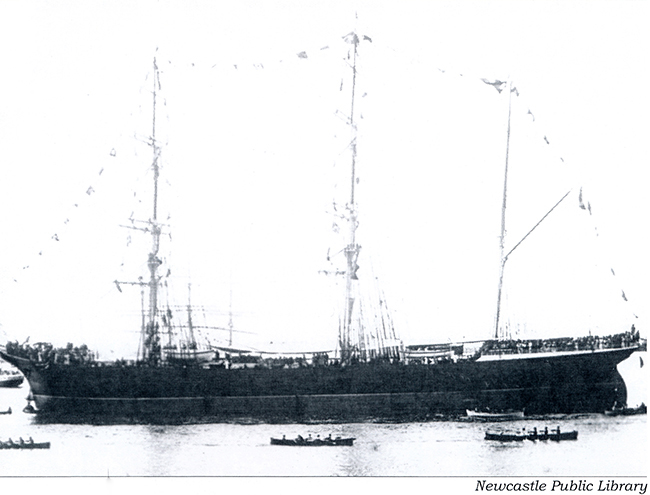

It was normal practice at Newcastle for a flagship to be moored at the 'Horseshoe' [a large deep area in the centre of the harbour where loaded cargo ships were moored before heading to sea] to mark the start/finish position of a triangular course. A flagship provided a vantage point for officials, invited guests and paying members of the public. NARs were sufficiently prestigious that shipping companies made their large passenger ships available as a flagship if they had one in the port at the time. Steamboats or steam launches were used as a flagship at smaller regattas.

Although some people viewed the racing from steamers and smaller boats most watched from the foreshore which was a congestion of wharves and railway lines. Organising committees were therefore obliged to obtain the approval of the Railway Commissioners for the public to use the wharf areas and verandahs of the railway goods sheds. Bullock Island Dyke must have been a popular vantage point for spectators if the plan to auction the rights to set up two publican booths during the 1878 NAR is anything to go by.

Another vantage point, at least for early NARs, was The Hill. A newspaper report on the 1877 NAR refers to spectators wending their way up Bolton Street which offered a pleasant view of the ocean "but our sagacious Borough Council has deprived them by erecting a hideous fence to obstruct the view". No one can argue with the panoramic view available and possibly many preferred to avoid the crowds along the foreshore. But being so far away meant that, apart from seeing boats racing in the distance, it would have been difficult to know what was actually transpiring. The fact that they made the effort suggests that it was worthwhile.

Four-oared gigs pass the flagship at the 1899 NAR

At many venues, numerous boats were moored along the course while others followed the competitors to the finish. The need to control the number of following boats would eventually be regulated by law.

Mercantile RC was the first Sydney club to compete at a NAR (1877) winning a race for bona fide amateurs in four oared string test gigs with cox. Otherwise, appearances by Sydney clubs were rare.

Races for ladies in NARs were few and far between. This was typical of the age when any form of outdoor sporting activity by ladies was thought to be unseemly. Nevertheless, there were a few. The first rowing race held in Australia for ladies may well have been at the 1873 NAR when NRC as organisers included a double scull race for ladies in watermens skiffs with cox. Although regarded as a success, the event was dropped the following year when the regatta's organisation reverted to a local committee, following a decision by NRC to discontinue its involvement.

Ladies' events did not feature in NARs again until 1905/06/07, then were discontinued. With ladies having gained something of a foothold, it is intriguing to surmise what went wrong. Female rowing was still relatively new so not yet fully accepted by the public. Certainly, the ladies were keen but few in number so race entries were limited and, because one or two ladies dominated Newcastle rowing at the time, other prospective rowers were bound to be daunted by the task. This might have been rectified if handicapping had been adopted. Whatever the reason, races for ladies disappeared from NARs.

When the Newcastle Jockey Club scheduled race meetings for New Years Day in 1894, 1895 and 1896 in opposition to the traditional annual regatta, the regatta committee decided against holding the event for those years. Whether the committee was just peeved that 'their' day had been hijacked or were spooked by the possibility of a serious reduction in revenue is unknown. Just how this clash of interests occurred is a puzzle since C H Hannell was then President of both organisations. Regattas on those years were run instead by the Stockton committee. Another interruption occurred in 1910 when the regatta was abandoned due to a strike and indifference. Just who 'struck' and who were 'indifferent' was not revealed.

NARs were not just an outstanding sporting event within the colony but also an important regional social occasion. Bands, side-shows, food and drink stalls and various amusements such as minature race courses with hand barrows and travelling skittling alleys gave them a carnival atmosphere; the presence of prominent citizens conveyed a sense of occasion while ships and boats, the shoreline and buildings were festooned with flags and bunting that added colour.

It was not unusual for as many as 10,000 spectators to be attracted to the harbour for the day but even this relatively large number from a small population was dwarfed in 1900 with a crowd estimated at 20,000. Spectators began arriving from early morning: locals by foot, horseback, carriage, omnibus and tram: day-trippers by special excursion trains from Singleton, Maitland and Wallsend, and by steamships from Morpeth and Clarencetown. They formed a mass of sightseers that left no vacant spot along the foreshore from the timber wharf to the pilot boat dock. Ahh. Those were the days.

The following photo provides some indication of the popularity of the event, particularly during the Colonial era. It also attests to the social of standing of the occasion with everyone in their best clothes - suits and ties for men, long dresses for the ladies and all wearing hats. That everyone wore clothing unsuitable for midsummer with no seating available and little shade suggests a high level of endurance.

After being a sporting and social highlight in the region for more than half a century, the last of the regular NARs was held in 1914. Following the outbreak of war in Europe, all sports began to struggle as more and more young men enlisted in the armed services. There was also the dilemma of whether or not it was right to continue with popular sports at a time when club members and fellow countrymen were fighting and dying overseas. This was reflected in a letter to the newspaper prior to the 1914 NAR suggesting that all proceeds go towards humanitarian relief in Belgium.

Large crowds were a feature of NARs.

In 1919, with the war over, the Mayor of Newcastle, Alderman Gibson, called a public meeting with a view to reviving the NAR. His efforts were only partially successful. Regattas followed in 1920 and 1921, however they were on a smaller scale than their illustrious predecessors. As before, they were held on the harbour on New Years Day. This time however the organisation was different with the committee comprising representatives of the Hunter River Professional Sculling Club and Port Hunter Sailing Club plus three citizens. The influence of the sculling club resulted in all rowing events being for prize money, effectively preventing any amateurs from competing. The decision appears to be counter-productive. Attracting Sydney clubs such as occurred in 1909 when Sydney University, Balmain, Enterprise and Mercantile competed in a race for regulation fours was more likely to achieve the stated intention of enhancing the status of the regatta. Various aspects worthy of note were a race for 6 oared gigs (a class of boat otherwise unheard of in Newcastle competitions); all double sculls had to carry a cox who was seven years of age or older; a four pair race was dependent on boats being available and a proviso that all rowing events, apart from one involving best and best boats, included a turn.

Several meetings were convened by Mayor R G Kilgour in late 1921 in an attempt to organise a regatta in 1922. Public interest was poor and the matter lapsed.

Subsequently, what was called the Newcastle Hospital Regatta was held on New Years Day 1928. As indicated by the title the regatta was a fund-raiser for the hospital. The program included seven rowing and two sailing races. Expressing a wish that the traditional event should continue, the organising committee invoked the name of the NAR (as did those involved with the 1920 and 1921 regattas) although it is doubtful that such a connection is valid. Their wish was granted although perhaps not quite as long as they had hoped. What would be the last regatta on the harbour for many decades was held the following year (1929) with just six rowing events and one surf boat race.

How had it come to this? There are many reasons. Certainly, once-a-year local regattas had to compete with an increasing number of other mainstream sports that were held every weekend. This regularity helped to sustain public interest, encouraging a habit of regular attendance by supporters, something that the occasional regatta could not match. Everyone can admire the efforts of devotees to foster and maintain their sport but for many the writing was on the wall. From the late 1800s observers both in Australia and in Britain were reporting a declining interest in rowing, particularly professional rowing.

That trend continued into the 20th century although George Town's world championship ensured interest continued in Newcastle for some years. By the mid-late 1920s however, press reports of rowing activities in the Hunter were increasingly rare. By the late 1930s, regattas were few and far between. Those that were held were smaller, involving a mixture of sailing, power boat and surf-boat races with just a couple of rowing races.

Perhaps the main reason was that the world was changing. Society no longer relied on boats for its transport needs. The advent of powered boats, then motor vehicles, meant that people no longer had any need to row so the once great pool of self-taught people who rowed, either for a living as professionals or for their own business or transport was disappearing. As early as 1883, the Town and Country Journal had lamented ruination of the watermen's profession by steamboats and launches over the previous twenty years. It was also noted that eights [most likely 8-oared cutters]were no longer used for umpiring at regattas "as in the past".

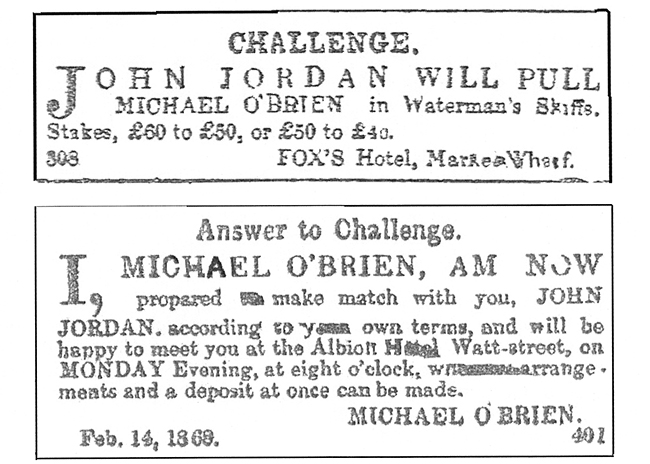

Professional Match Racing

Apart from local regattas there were three other types of competitive rowing events. The first and, at the time, most prestigious, were the ad hoc match racing contests held between two professional rowers for stake money. Match racing produced the various champions of the day from local to colony (state) to international level. The ritual involved a rower issuing a public challenge through one or more newspaper advertisements either generally or to a particular person.

Not all negotiations were as succinct or dispassionate. The following is part of an exchange that ran in the Maitland Mercury in 1859.

"To Mr. McPherson and his Pulling Crew.

We own you beat the Uncle Tom with the unequal boat. We don't want your odds; as for our laurels, we can gain them any time in an equal boat . There are two of you I have boat single handed. As for touching on the raw, Mac, I never was boy beaten. A PHILP, junior."

This reply came the following week.

"Mr A PHILP, JUN.

In reference to your evasive answer in the Mercury of 16th instant, wherein you endeavour to draw me into the contest, I beg to inform you, as you seem inclined to have a touch of me, I am willing and ready to meet you. You find two equal boats and I will row you with a pair of sculls - fifteen pounds to ten pounds - the same distance as the sculls race at the Anniversary Regatta.

It appears to me that neither you nor your crew have the least idea of pulling without having a decided advantage. I certainly consider, and I will leave it to public opinion, if you have been fairly dealt with.

In conclusion, if you intend doing anything, come to the scratch like a man; if not, I must decline having any further newspaper communication with you. You can always hear of me or my "pulling crew" (as you term them), at Mr Ewen's, Raymond Terrace.

WILLIAM McPHERSON Williams River."

Challenges by one crew against another were uncommon. Any that did occur were usually between local crews for money with no title involved.

The challenger usually nominated an amount or range of stake money. At the lower end of the scale this might be just a few pounds. Occasionally, the stakes included the boat used. As rowers improved their standing they would then challenge others of a similar status, especially those who held a particular title. Naturally, this entailed a corresponding rise in stake money.

Champions also rowed in match races to gain fitness and experience without necessarily staking their title. For the same reason, they participated in regattas both locally and at other centres up and down the coast. Local regattas were not the avenue through which professional championships were won and lost.

Championships could only be won from the champion in a private match in which the articles of agreement stipulated that the championship was at stake. Thus, champion rowers earned their title by challenging and defeating the incumbent champion. Title holders then had to face challenges from other aspirants - rather like boxing today or gunfighters of the old west, although the stakes were somewhat higher in the latter.

In theory, professional championship holders were expected to accept any reasonable challenge, however there was no rule as to when or whose challenges were accepted so titleholders could dictate terms and conditions. George Town revealed that, as challenger, he had to agree to anything Canadian world champion Jake Gaudaur asked for in terms of race location and conditions. Following a meeting in 1906 involving Australia's top scullers when rules were adopted governing sculling championships, incumbent champions were given three months in which to accept a challenge then had to defend the title within six months. At the same time, it was also decided that the stake for championship contests between Australians was to be not less than £200.

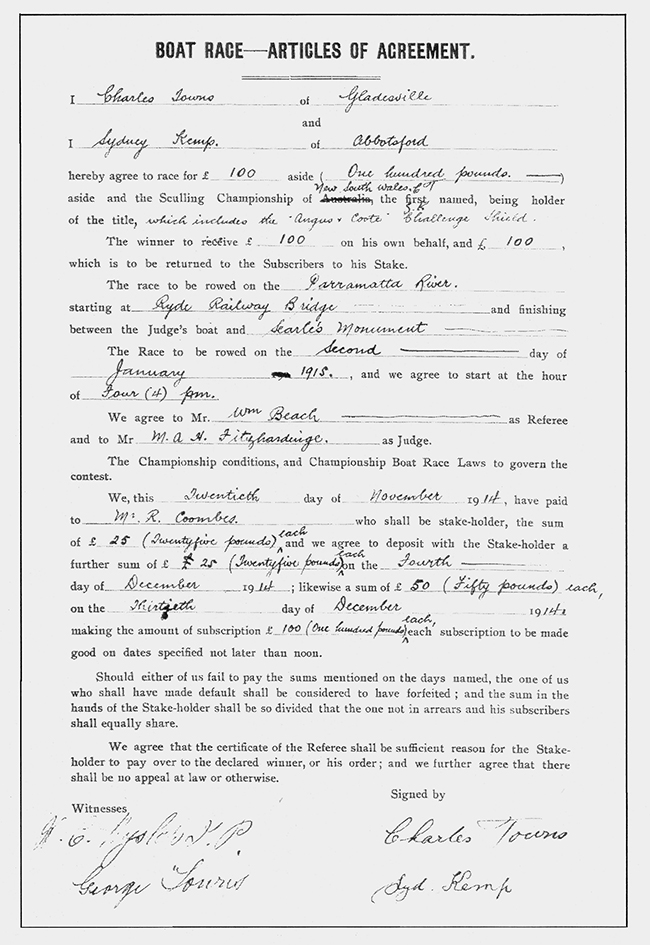

Once a challenge had been accepted, meetings between the rowers or their representatives followed to negotiate organisational and match arrangements. These included the amount of stake money (that was held by a mutually acceptable neutral stakeholder to be paid to the winner); the course to be rowed, boats to be used, selection of officials, rules of the race, payment of expenses and other relevant details. These were incorporated into signed Articles of Agreement that bound the rowers to the match. An example of one such Agreement - the Charlie Towns v Sydney Kemp match - for the NSW sculling championship, is shown below.

By then (1914), the format was standard and would have applied whether for Australian or World championship contests. Appendices to the Agreement contained conditions appertaining to the conduct of Championship events as well as Australian Championship Boat Race Laws. Participants could, by agreement, vary those conditions. For instance, in a race between Thoroughgood and Pearce for the Australian title in 1909, Pearce (the challenger) agreed to pay Thoroughgood £20 towards his expenses. In an earlier match between George Towns and Tresidder in 1904 the former negotiated an arrangement whereby if he lost he would have received 75% of the net steamer receipts otherwise it would be split 50-50, the same as gate receipts.

Champion rowers were often supported by benefactors who would pay stake money as well as provide financial support for their training and coaching. Otherwise they had to have private means or rely on fund raising activities. Where championships with large stake money were involved it was the usual practice to lodge periodic instalments. Presumably this practice allowed each rower time to raise their stake whilst keeping the forthcoming match in the news thereby increasing public interest. If a titleholder failed to raise the agreed amount, the title was forfeited to the challenger. For many professional rowers and their backers, there was a great deal of money to be made from (successful) side bets. For example when Australian world champion sculler Henry Searle defeated the challenger William O'Connor of Canada in 1889, the purse was for £500 a-side but Searle was thought to have won £30,000 in bets. As discussed earlier, betting on races by the public was popular and widespread.

One of the few professional rowers to reveal their income from the sport was Canadian Edward Hanlon, world sculling champion 1880- 84. In an 1883 interview for the London "Sportsman" he said that he gained $US33,000 from stake/prize money with a further $US21,500 from betting winnings. The period involved was not stated but was probably, from 1873, i.e. over 10 years.

The return for professional scullers was not great when their expenses were considered. They needed a racing boat, several practice boats and some kind of boat for his trainer or sculling companion. To have any chance in a race, he and his trainer usually had to relocate to be near a suitable stretch of water for a lengthy period before an important race. For challengers for the world title this usually meant abroad. Pre-training could last for up to six months, some or all of which could be full-time during which they gave up everything else. Their backers usually expected to get a financial return which had the effect of emphasizing the importance and detrimental influence of betting. Few amateur scullers appear to have turned professional. One suspects that financial backers were reluctant to support unproven amateurs in preference to hardened professionals. Limited stake and prize money available may also have played a part.

A great drawback for the sport was the difficulty of collecting gate money. Thousands attended but it was often impossible to charge people for standing on a river bank or harbour foreshore. Prior to challenging Ben Thoroughgood for his Australian title Sydney's Harry Pearce claimed that it was impossible to get a good gate at Raymond Terrace. For his part, Thoroughgood was reluctant to hold the contest on the Parramatta River as he found it difficult to obtain financial backing anywhere but on the Hunter.

Professional rowing began to decline in the late 1890's. The decline was due to a variety of reasons such as loss of public faith in the integrity of contests, competition from other sports, withdrawal of financial backers and races being too irregular to maintain public interest. Over a relatively short time the skills of the professional rower became redundant once powered boats and motor vehicles replaced the use of rowed boats for many transport tasks. This gap was filled (very well, most dispassionate observers would agree) by amateur rowing clubs that provided a grass roots system producing new generations of rowers. Emergence of a few professional rowing clubs in the late 1800s-early 1900s was a case of too little, too late.

Professional rowing as a separate entitity disappeared from the Newcastle scene by the 1930s and from Australia by the late 1950s. Indeed, it had probably expired by 1938 after Australian Bobby Pearce, who had won the title in 1933, defended it for the second time. With war intervening, Pearce did not have to defend the title again until retiring undefeated in 1948. Subsequent champions were not highly regarded and their contests were accorded little credibility. World Sculling Championships, which had been contested by the greatest scullers of the age since 1831, ended in 1957.

Amateur Rowing Clubs

The third form of rowing contest was, of course, those conducted by amateur rowing clubs. Initially, club contests were internal with occasional races between a few crews or scullers plus an annual regatta comprising between three and six events solely for club members. It was only in the 1880s that clubs started including a race or two in their regatta program for members of other clubs. Club members could also compete at local regattas either in events for (bona fide) amateurs or races specifically allocated to rowing clubs, if programmed.

Clubs functioned separately from the pre-existing loose regatta structure but fitted quite comfortably within it. For example, NRC's inaugural regatta in March 1871 was a five-event program that included four races for club members and one for watermen who, obviously, were professionals. Several Newcastle Annual Regattas in the early 1870's provided separate events for members of NRC (bona fide amateurs), people involved in manual labour (amateurs) and watermen (professionals).

The relative ease with which a rowing club such as Newcastle was accepted and catered for by local regatta committees is not surprising. In the main, they were run by the same people. Prominent citizens who through a love of rowing served on one or more regatta committees were also inclined to become involved in similar capacities with rowing clubs. It appears that rowing clubs, in catering for bona fide or gentleman amateurs, reflected their own values such as the notion of competition for the love of it rather than for money. Clubs provided interested non-professionals with the opportunity to practise and develop their rowing skills on a regular basis. For most amateurs, this had not been easy beforehand. Another important factor was that clubs did not threaten existing interest groups so the status quo was maintained.

Emergence of "amateur" rowing clubs was closely followed by the formation of colony (state) associations; the Victorian Rowing Association (VRA) in 1876 and the NSW Rowing Association (NSWRA) in 1878. The latter was referred to by one newspaper as the "latest novelty". This was undoubtedly due to the fact that at the time NSWRA was simply a committee made up of representatives of the only two clubs in Sydney (Sydney and Mercantile) with its main, perhaps only, function to arrange inter-colonial contests. State associations took years to establish both their role and their credibility, eventually adding much needed regulation and coordination to competitive rowing -within the amateur component anyway.

Over time, clubs affiliated with their association although initially, apart from the possible (and costly) opportunity for their better rowers to represent the state, they saw little benefit in affiliation since they could hold their own races as well as participate in local regattas. When the NSWRA began organising its own regattas (1880) they were in addition to the long-established system outlined above although, for many years, they were limited to Sydney venues; Parramatta and Sydney Harbour.

The pinnacle for amateur rowers in Australia during the colonial era were the popular inter-colonial contests. They commenced in 1863 with just two crews, Sydney and Victoria, rowing 4-oared gigs. After just four of these gig races, the format was changed in 1878 to an Soar contest to be held annually between NSW and Victoria. Later, other colonies were invited to participate. The event was renamed the Kings Cup in 1920. The first Australian amateur sculling championship was held in 1895. Top rowers in the colonial era would have dreamed about the Wingfield Sculls for the British amateur sculling championship (from 1830) the Henley Royal Regatta and the Diamond Sculls (1844). Subsequently, the Olympic Games (1900), Empire/Commonwealth Games (1930-1962) and the World Rowing Championships (1962) became significant international events.

Promoted Regattas

A fourth but rare form of regatta were small events put on by local businessmen for their own reasons. One such was John Hannell who ran boat races at Hexham in the mid-1800s to attract customers to his hotel, the Wheat Sheaf Inn. Another was Mr E C Lightfoot who ran the Hexham Handicap probably for the same reason. One of his was held on a 'pay Saturday' in April 1900. It consisted of two events, both in best-and-best boats (single sculls). The first, with an entry fee of 10/-, was for allcomers over a 2 mile course for £10 and a silver cup. The second, with an entry fee of 4/-, was for amateurs over 1 ½ miles for £4 prize money.

Footnotes

- "Regatta" originated in Italy, almost certainly and inevitably in Venice around the 13th century. The word referred to spectacular water festivals involving boat races, aquatic displays and entertainment. The term was adopted in Britain in the 1770s.

- Throughout the colonial era and until the mid-20th century, Australia used Imperial measurements. Conversion factors to decimal units together with the relative value of the then currency from pounds, shillings and pence to dollars and cents are given in Appendix B.

Part 1 pages: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7

Previous < Introduction