History of Newcastle Rowing Club

Part 1 - Rowing in Colonial Australia (continued)

Part 1 pages: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7

Newcastle's Champion Rowers

Newcastle, once awash with expert oars-men and-women, has produced some of Australia's best scullers. Early champion rowers include:

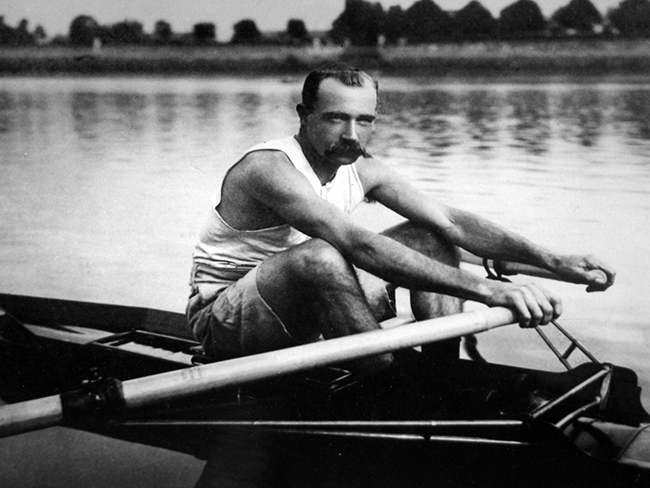

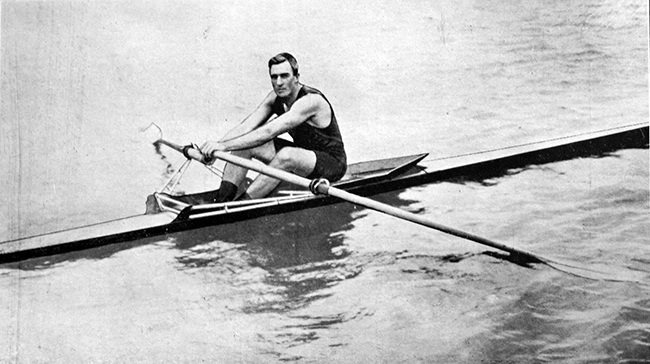

George J J Towns (1869-1961), the 'Hunter Crack', is undoubtedly the most successful oarsman the Newcastle region has ever produced. He won the Sportsman Challenge Cup for the championship of England in 1899, successfully defended the title in 1900, became the world champion sculler in 1901, held the title until 1905 then regained it again in 1906 before retiring in 1907.

George learned to scull as a boy when he rowed his family's farm produce from Dempsey Island four miles to Newcastle. He and his seven brothers also had to row to school each day. His imposing record commenced immediately he began rowing competitively when just 14. In his first race, for youths under 16, he came second. In races for youths under 19 he secured six firsts and five seconds. At 20 he won five all-comers (i.e open) events. As a "dark horse" he came third out of 21 professionals in the prestigious Parramatta River handicap sculling championship event in 1892.

George acknowledged that he was not widely accepted as the top Australian candidate since he had not defeated former world champion and fellow New South Welshman James Stanbury. Nevertheless, determined to win the world championship he went to England in 1895 competing there for five years to improve his technique and stamina. During that period he was very successful against local opposition winning the championship of England in 1899 and 1900. Indeed, he might have won the 1898 final against Englishman WA Barry had his boat not struck a submerged log when he was leading the race and sank, a minor detail omitted from British accounts. Nowadays, nautical experts using powerful modern computers to analyse the technical data are almost unanimous in their belief that, if a boat sinks during a race, it is unlikely to win.

George Towns

At the same time as he was preparing for the England Championship in 1900, George trained C V Fox to win the Wingfield Sculls, England's amateur sculling championship. Obviously at a loose end, in 1901 George and two friends rowed a triple scull from Oxford to Putney (London) a distance of 104 miles in 13 hours and 59 minutes.

He subsequently won the world sculling title and £1000 pounds (£500 a side) from Canadian Jacob ('Jake') Gaudaur in 1901. The English Field magazine noted his "light and clean stroke". Elsewhere it was said he rowed with long sweeping strokes resembling the late, brilliant Harry Searle. The Sydney Mail on the other hand avoided any technical jargon. It described George as a "real" Australian, "handsome, manly and determined" and "one of those men who seem to get larger the more clothes they take off". Now that is a sound basis for winning a world title in any sport.

The astounding aspect of George's success was that at 5' 8 1h" [174cm] tall and weighing just eleven stone four pounds (71.7 kg) he was not big. Today he would be classified a lightweight rower. George is an excellent example of a good little man with technique and determination defeating a host of good big men.

An interesting aspect of the win was that rather than use a 31 foot boat similar to that rowed by his opponent and preferred by most professionals, George used a shorter (25 foot) boat called a 'stump' outrigger designed by an Australian boat builder, Chris Neilsen. George is also credited with introducing left and right-handed oars to England. Flattening the sleeve on the underside of the oar helped keep the oar square in the water and reduced the tendency to over rotate.

He returned to Australia in 1902 with the title and a new wife. He was welcomed by the rowing fraternity in Adelaide then received a public reception in Sydney hosted by the Lord Mayor with all the top rowers of the day in attendance. Arriving home in Newcastle he was met by the Mayor and 7000 people to be presented with a gold medal and a purse of sovereigns.

In 1904, George (wearing navy and light blue colours), successfully defended his title against fellow Novocastrian, Richard Tresidder (wearing pale blue and white) who had won the Australian championship from Harry Pearce the previous year.

George lost the title to fellow Australian James Stanbury in 1905 then regained it in 1906. This time one Sydney reporter claimed that he had changed his style, pulling more quickly with a much shorter stroke so that it was not as attractive as when he first won the title. On the other hand a Newcastle Herald reporter, having regularly watched George in training demonstrated the value of expert opinions by stating that he was rowing a longer stroke. Whatever stroke length he actually used, George was three lengths behind at the 21h mile mark and seemingly well beaten by the favourite. Showing his renowned will-to-win, George pressured Stanbury, overhauling him at Gladesville and going on to win by six lengths. The race was in front of 50-60,000 people including numerous Novocastrians who had taken advantage of the cheap excursion train. George's supporters made up the majority of spectators on the larger steamship for which they were charged one pound (£1) for the additional comfort. Several smaller steamers were cheaper costing just ten shillings (10/-) or five shillings (5/-). As well as winning his opponent's £500, he received an equal amount from his backer, S Arnott. He also received £99.16.3 being the challenger's share (25%) of the steamer receipts. If George had a little flutter on himself it was not revealed to the press.

Following his victory over Stanbury, George's brother Charlie was the first of all George's likely opponents to lodge a deposit thus giving him the right to the first answer. The possible match was not taken seriously by the public nor given any credence within rowing circles. George's subsequent retirement as world sculling champion in 1907 surprised nobody and, having effectively refused his brother's challenge, the title passed to Charlie. Such a situation would be thought of today as curious, even suspicious, but that was not the case then. It should be borne in mind that, at the time, professional rowing had no formal organisation or structure. In the absence of a governing body regulating the sport a title-holder could dictate how, with whom and under what conditions titles were contested. In his first defence of the title Charles lost to a New Zealander, William Webb.

George returned to England in 1909 in an unsuccessful attempt to regain the Championship of England. Before he left for home his English admirers held a dinner in his honour from which we learn a little more of what made George a successful rower. Although smaller than his top class opponents he was said to possess a faultless technique. In particular they praised his dogged persistence; a much admired ability to "hang on", that friend and foe alike believed enabled him to win many of his races. In response, he related the story of his first match. When just eight years old, an argument with a school mate over who was the better man was decided by a boat race. Thus one moonlight night on the Hunter River he won his first race. Clearly, he was a born rower. They discussed stake money amounting to pounds but settled on fourpence each. Evidently, he was also a born professional rower.

At another dinner organized by The Sportsman, George was presented with a cheque for £24. 15. 9 donated by his English supporters. This was on top of a previous gift of £100 a few years earlier. He was also presented with a vellum [a superior quality parchment, most commonly of calfskin] containing the signatures of many of the world's best oarsmen. His wife's lady friends presented her with a solid gold bracelet. George remarked that they could not have made more fuss of him had he won.

George established a successful boat building business on the Parramatta River at Gladesville in 1903 which he ran until the 1970s. His business built seventy-five percent of all the racing shells used in Australia at the time as well as boats being built for clients in many other countries. Bobby Pearce won a gold medal at the 1928 Olympics in a one of his boats. He also went on to coach new generations of rowers -both professional and amateur including NSW crews, at least one Australian Olympian and one world champion sculler. George was President of the NSW Rowing and Sculllng League (1917) and was instrumental in formulating standard regulations to govern world sculling championships. Between 1909 and 1919 George made his shed available to the NSWRA when it was unable to afford a suitable premises for a headquarters and boatshed.

In the 1960s, George acknowledged that modern rowers were rowing faster which he attributed to better boats and scientific training. However, he reckoned that for stamina and skill, the old-time champions would have matched the best of the modern rowers.

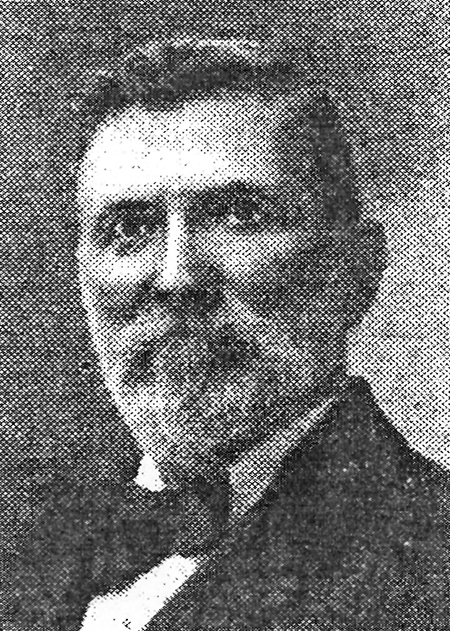

Charles F Towns (1880-1970). As explained previously, Charles inherited the title of world champion sculler from his brother George in 1907. Despite his early loss of the title, Charlie was a brilliant sculler in light skiffs with an outstanding record in the Hunter, the North Coast and Sydney. He held the NSW sculling championship for a time (probably between 1913 -1915) and defeated some of NSW's best scullers such as Peter Kemp, Harry Pearce as well as fellow Novocastrans Richard Tresidder and Ben Thoroughgood.

Charles Towns

Richard Bernard Joel Tresidder (1871-1920), of Carrington and later Mayfield was a broad shouldered fisherman with strong upper body who rowed with skill and stamina. After his first sculling race in 1889 he raced the top local rowers including the Towns' and the Hickeys' throughout the 1890s-early 1900s. Although his earliest successes were in doubles, his breakthrough as a single sculler came in 1896 when he defeated the better credentialed "Hunter Hurricane" Jim Ford over about three miles on the Raymond Terrace course for £50 a side.

In March 1903 he rowed Harry Pearce on the Parramatta River for the Australian sculling title3. He was accompanied by a big contingent of supporters including many of Newcastle's best rowers. It was said that Newcastle people "had come down to a man" and were not afraid of stacking money on their representative taking bets for between £1 and £100. He won by six lengths earning the right to challenge George Towns for the world title.

Richard 'Dick' Tresidder

As both were Novocastrians, there was widespread speculation that the match would be held locally. That wasn't to be and the race was held on the Parramatta River on 30 July 1904. Immense interest in the first race for the title to be held in Australia for twelve years drew an estimated 90,000 (including about 1000 Novocastrians) spectators who watched either from the bank or on following boats. For some inexplicable reason Tresidder was favourite with the Novocastrians, his supporters prepared to back him for up to £1000. Some supposedly even mortgaged their homes for the purpose. If true, it turned out to be real bad judgement as Towns won by 20 lengths.

Following Webb's win over Charlie Towns, Tresidder quickly challenged the new champion. The race that was held on 25 February 1908 over a 3 1/4 mile course on the Wanganui River in New Zealand. Even though Tresidder was supremely confident beforehand he was beaten by 2 1/2 lengths in a time of 20 min 28 secs. After the race, Tresidder rowed the eight miles back to Wanganui. He later said that Webb deserved to win being a better sculler than he had anticipated. Observers felt that the ten-year age difference benefited the younger Webb.

Soon afterwards, Tresidder announced that he had no intention of ever rowing again. He handed the Australian Sculling Championship over to another Novocastrian, Ben Thoroughgood.

A fascinating feature of Tresidder's contest against Webb in New Zealand was that his racing singlet bore a kangaroo motif. Nowadays, linking native animals with Australian sporting teams is common but this was 1908. The only reason Tresidder would have adopted the symbol was to identify his nationality. Whether it was a first or whose example he might have followed may never be known.

Ben Thoroughgood (1869-1927), a Stockton resident, was another top class rower in the late 19th - early 20th century. He won his first race at a Stockton Regatta for youths under 16 in heavy 22 ft boats with fixed seats. Unbeaten, he went on to become Australia's best heavy boat oarsman and de facto champion to the extent that for a considerable time he could not get a match.

Ben Thoroughgood

He only took up rowing the much lighter outriggers in 1906 when he was 36 years old. Within a few months he rowed Alf Worboys of Wallsend in outriggers over three miles at the Raymond Terrace course for a £200 stake. Beforehand there had been speculation as to how Worboys, a prettier sculler, would go against Thoroughgood, a big man possessing great stamina. As it was Thoroughgood's first race in outriggers, it was not surprising that he tended to revert to a heavy boat stroke. Nor had he mastered the sliding seat. Nevertheless, he won with a stroke said to have a crisp catch and a hard finish in which he brought his sculls well home. At 37 he rowed against Dick Tresidder in outriggers. Although losing, as the last challenger he inherited the Australia sculling title in 1908 when Tresidder retired.

Thoroughgood successfully defended the title against William Fogwell and and George Whelch before losing it in May1909, when at the age of 40, he was defeated by Harry Pearce, who had lost the title to Tresidder in 1903. In preparing his challenge Thoroughgood was hampered by reluctance of his usual backers to assist in raising the agreed amount of stake money to match that of his opponent. Even raising the deposit proved difficult and the money was only raised with a couple of days to spare. This reluctance was attributed to the reticence of his usual backers (who, incidentally, met at the most unlikely venue -Stockton's Boatrowers Hotel) to support his racing in Sydney. However, the Newcastle Herald pointed out that Thoroughgood had rowed at Raymond Terrace on his previous five races with little return from gate money.

From about 1910 to 1914 there was a lot of heavy boat rowing in Sydney with a number of claimants for the NSW champion title. Amid this conjecture, Thoroughgood's unbeaten record in heavy boats had been forgotten. Probably as a result of the renewed interest in heavy boats, the Rowing and Sculling League (which had been formed in October 1913 to control professional rowing and sculling) established several championship events for professionals including a single sculls heavy boat championship of NSW (in 18 foot boats). A race to decide the issue was held over a 2 mile course on Middle Harbour in October 1914. With Thoroughgood not fully prepared, Arthur Pearce won the title. However, just a few months later (January 1915), 'Big Ben', then a 45-year old veteran, rowed Pearce over the same course for the title and £25. This time, properly prepared, he won, or some would argue, regained the NSW heavy boat championship.

He lost the Australian heavy boat championship title on the Hunter River at Stockton in May 1916 to William (Billy) Ripley, a fellow Novocastrian. Thoroughgood retired from active competition after losing a rematch the following month. Great pride was expressed in Newcastle not only for his long and distinguished career but also his admirable sporting qualities as well as his (then) unprecedented involvement in championship events until well into his forties. He became President of Elmbank RC located at Stockton.

Thoroughgood's record is outstanding yet it seems likely that it could have been even better. Peter Kemp, world sculling champion in 1888, was just one of a number of top rowers who believed that Thoroughgood had the ability to be a world champion. Sadly, that potential was never realized.

William Hickey (c1844-1891) was Australia's top rower in an earlier era. William was widely regarded by many as superior to any other rower produced by Australia during the latter half of the 19th century; a list that includes world champions such as Trickett, Beach, Kemp and Searle. Certainly, he ranks with the nation's greatest.

As with his younger brother Richard, William developed his skill delivering milk by rowboat twice each day from Dempsey Island to Newcastle. Almost invincible in the Hunter, William, made his Sydney debut on Port Jackson at the Anniversary Regatta in 1865 winning a race in light skiffs. Later, as a farmer and little known in Sydney rowing circles and therefore not highly rated, he defeated Richard Green in June 1865 in a licensed waterman boat for a £170 stake to become the Australian champion rower in watermens skiffs. Within days, as a tribute to his win and the honour it reflected on Newcastle, his supporters gave him an outrigger wager boat named "Rose of Australia". Thirty three feet six inches long and weighing 40 pounds (lbs) (35 lbs without riggers), it was described as a "beautiful specimen of its class".

However, to be the Australian sculling champion he had to beat Green in best boats (racing sculls). He did that in January 1866 on the Parramatta River in wager boats for a stake of £200. It was just his second race in a light outrigger skiff. (Note the various terms that could be applied to the same boat). The records are contradictory but it seems most likely that he held the championship until defeated by Michael Rush in December 1870.

William effected what was regarded, even 50 years after the event, as the most remarkable race ever over the championship course on Parramatta River. In December 1865 he rowed Harry White, the crack English rower, in wager boats for £100 a side. Although Hickey was 6 to 4 on favourite, White's imposing record meant that he had many supporters. Briefly, both rowers got away together with Hickey taking a slight early lead. Both boats were together for a mile when the race unfolded like the script of a theatrical drama. Off Kissing Point, Hickey fouled a moored boat giving White a long lead. When Hickey got into his stroke again spectators were treated to one of the best if not the greatest feat of sculling ever witnessed on the river.

William Hickey

Rowing in great style, he bent to his work and at two and a half miles had reduced White's lead to just half a length. "Could Hickey last?" was the question as the excited onlookers cheered on their favourite. At the Point, Hickey slipped up on the inside and in just a few lengths forged into the lead. From then on he had it all his own way and at the winning post (The Brothers) was a good three lengths ahead, winning in 24 minutes 50 seconds. Subsequently, William was described as " ... a most extraordinary puller. He has wonderful strength and activity with indomitable pluck. His feat (winning the race) was of no ordinary character".

Stake money for his rematch with Green in 1867 was £200 a side. For one of his contests in heavy boats against arch-rival Rush in 1870 stake money was £500 (almost certainly £250 each), He lost his Australian title to Rush later the same year when the stake was £200. Even so, Hickey's confidence was such that in 1871 he announced himself as "Champion of Port Jackson" and open to row any man in Australia in any class of boat for £100 or more.

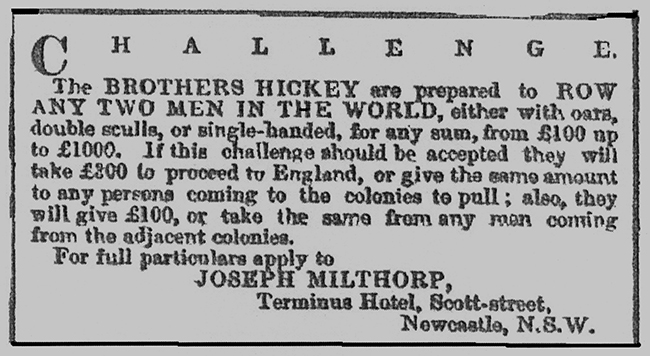

Regarded locally as unbeatable when either rowing or sculling together, in 1869 the two brothers issued what is possibly the most famous challenge in Australian rowing.

Such a challenge was audacious in its scope - anyone, anywhere, in singles, doubles or pairs. With no championship involved, the stakes, for the time, were enormous.

Later, James Renforth the English and world sculling champion offered to row William on the Thames or Tyne for the world championship and £1000 a side. Naturally, this caused great excitement in Newcastle, ours, that is, not theirs for, coincidentally, Renforth was from Newcastle too -but the English one. Even with assistance from a local committee formed for the purpose and the opening of public subscriptions, the estimated £1200 necessary could not be raised so the challenge lapsed. We will never know how he would have fared but he was considered by many knowledgeable judges who were familiar with the champion rowers of the day including Canadian Edward Hanlon (world champion 1880-84) that William was the "best man we ever had and perhaps the best man that ever sat in a boat".

Whilst William Hickey's record was as a sculler in light skiffs was impressive many of his contemporaries believed he was even better in the "good old days" of heavy boats with fixed seats. These required great strength to row: skill was secondary. In a race between Hickey and Rush in 1870, the farmer's boat was 33 ft long and 4'10" wide; the latter's 34' long and 5'2" wide. When one considers that 22' skiffs were usually used for as singles and doubles, racing such large boats had to be hard work. Obviously, whoever called them the "good old days" had never rowed one.

William's brother, Richard Hickey (1845-1933), was an oysterman. As a waterman, he was automatically classified a professional rower (William was a professional because he rowed for prize money). Richard was very successful at regattas in the Hunter and in Sydney.

Richard Hickey

Richard started racing when he was sixteen and his first win was against his brother. During his career, Richard had wins over Elias Laycock and Green but his ability was most amply demonstrated at the Newcastle Annual Regatta in 1877 when, although described as an "old [he was 32] veteran sadly out of condition" he defeated (Australian) Edward Trickett who, the previous year, had become the first champion of the world. It was subsequently reported in the press that the steamer 'Perseverance' crossed Trickett's bow giving him its wash. The action was described as either deliberate, in which case it was shameful and a disgrace to Newcastle, or careless. Hickey responded promptly with a letter to the paper claiming that the boat had in fact crossed Trickett's stern so giving him a stimulus and an advantage over Hickey. Pointing out that steamers were a nuisance at all regattas and that he had been similarly affected in the past, Hickey challenged Trickett to a rematch for £200 over 3 miles to be held on the Hunter River within six weeks. The offer was not taken up. His last race was at Stockton which he won with a handicap of 85 lbs. Richard coached NRC crews on occasions and often acted as cox for NRC crews at regattas.

Following their retirement from competitive rowing, both Hickey brothers were involved as committee members and race officials in the Newcastle Annual Regatta.

John Robert Towns (1882-1968), was a younger brother of George and Charlie Towns who emulated his siblings with an impressive winning record as a young man in regattas in Newcastle around the turn of the century. Moving to Sydney, he was a member of Sydney Mercantile RC when he represented NSW in the race for amateur sculling championship of Australia in 1908 before winning the title in Brisbane in 1909. Although winning it was reported that he did not row well, having a bad fault of 'hanging' at the catch and finish.

John Towns from 1908 Interstate Championships program

Other top rowers

Tom and Cornelius Croese, M Bedford, Martin Jordan, W Hughes, George ('Podgy') Hughes, Edward Sheppard, Harry and Tom Muncaster and Tongue were just some of the other top ranked Newcastle rowers of the late 1800's - early 1900's.

W Hughes was involved in an interesting race in 1888 when he rowed on the Parramatta River course against Henry Searle for £100 a side. (Later in the year Searle would win the world championship). Just after the start, Searle's boat sprang a leak forcing him to stop at intervals and use his cap to bail out the water. When the boat's bung came out he had to stop bailing and use his cap to plug the hole. His boat, overwhelmed by its defects, still took in water but, in the tradition of all true thoroughbreds, only sank after it crossed the finishing line. Despite these difficulties and having given Hughes a 10 second start Searle still won by 30 seconds. The result should be taken as confirmation of Searle's greatness rather than any adverse reflection on Hughes' ability. He was a very accomplished rower (otherwise he wouldn't have been rowing Searle at all) and £100 was a lot of money.

Often, rowing was a family affair with the Towns brothers the most prominent example. Apart from the three discussed above, Herbert, Arthur, Theo, Norman and Eldred also competed. Naturally, some were better than others. Neither Walter nor Emily appear to have followed their sibling's footsteps. In any case, it hardly seems likely the farm could possibly have grown enough for all the siblings to row produce to market every day.

Aside from a few exceptions same-family rowers were men. Most notable of the exceptions were the Hickey family, all of whom, sisters included, were first-class in a boat. In the early twentieth century, Ben Thoroughgood and his sister Rose (Woodbridge) were the best of a strong group of rowing families that included names like Croese, Jordan, Latham, Hyde, Dempsey, Muncaster, Ross, Ripley, Marjorybanks and Moncrieff.

All of the champion and or other top rowers from Newcastle during the colonial era were professionals. Even a rise in numbers and quality of amateurs following the emergence of clubs failed to produce an individual capable of dominating amateur racing in Newcastle during the period 1870 - 1901, much less enjoying any sustained success at NSW or higher level.

This was an interesting contrast with Australian performances

internationally. For 22 of the years from 1876 to 1907, seven Australians (Trickett, Beach, Kemp, Searle, McLean, Stanbury and George Towns) held the world sculling championship. All were New South Welshmen; no Victorian even contested the title. Yet, to the enormous frustration of NSW supporters who were perennially over confident, out of thirty-one eight-oared inter-colonial races during the period 1878 to 1907, twenty-five were won by Victoria. Whatever the reason, based on the inter-colonial results, amateur rowing in Victoria during the colonial period was substantially stronger and probably better organised than in NSW.

Unfortunately, apart from John Towns, none of the Newcastle rowers mentioned would have been able to row for NRC even if they had wanted to. This is because of the strict and complex rules defining "professionals" or "amateurs".

Footnotes

3. Stuart Ripley, in his book 'Sculling and Skullduggery', 'A history of professional sculling', makes the interesting point that "previously there had been no such tiltle or race" and that is was the view at the time that backers and their rowers could invent a title race. Thus it was that many champions were born.

Part 1 pages: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7

Previous < Introduction