The Boys from the Rush Beds

The History of the Ballarat City Rowing Club 1870-2004 and Incorporating the Early Development of Lake Wendouree 1860-70, By Kathryn M Elliott

1. Prelude

The Deleopment of Lake Wendouree and of Rowing

“Our Lake is to Ballarat what our beautiful Harbour is to Sydney. It is our pride and joy and our principal source of recreation. Nothing could compensate us for the loss of that oasis in the desert in the absence of which all the surrounding mansions, villas and smiling lawns and gardens would soon present a scene of desolation.”

Thus started an article in the Ballarat Star newspaper in 1870. Indeed, what would Ballarat be without this “gleaming jewel” in its crown? What would Ballarat be like if the vision of a few persistent rowing men had not been realised? It could have so easily happened - the Swamp remaining a swamp or turned over to cultivation and then residential land. It was only the persistence and determination of one or two rowing men of the time, which ultimately tipped the scales in favour of developing an “ornamental” sheet of water and arguably Ballarat’s greatest icon. From the time Robinson (Bob) McClaren envisaged clearing the Swamp and rowing on it, it took seven long years of arguing, striving and overcoming nature to finally achieve that beautiful clear sheet of water we see today. From 1864 until 1870 struggling against drought, lack of resources and factional squabbles between Eastern and Western Councils, it is indeed a wonder that his vision ever became a reality. In order to understand the development of rowing and particularly the formation of the Ballarat City Rowing Club it is important to understand some of the background to the metamorphosis from Yuille Swamp to Lake Wendouree.

The Pastoral Idyll 1838-1851

In the beginning of white settlement of the area in 1838, there was the “Black Swamp”- a shallow, reedy swamp on a rich alluvial flat. Local aboriginal tribes would have found a pleasant resting place of green rushes, drooping she-oaks and white-trunked eucalypts. Birds of all kinds in profusion, quiet groups of grazing kangaroo and pools of fresh, clean water. An idyllic watering hole that made an excellent resting place for both the indigenous population and the pastoralists who had begun exploring the area. These first white settlers knew the Swamp as a good camping place - with water for the bullocks and travellers and a point at which a long journey might be pleasurably broken providing some ease on the long journeys across the vast, mostly empty expanse of the new colony.

Some of the very first settlers, the Learmonth brothers of Ercildoune, noted that in some years the Swamp would dry up. This happened in 1834 and 1835 but did not greatly affect the sparse population that wandered by or the local indigenous population. They simply moved on and found another watering place.

Scottish cousins William Cross Yuille and his cousin Archibald along with Henry Anderson were the first settlers on the 10,000 acre Ballarat run. They arrived in March 1838 with 5,000 head of sheep and settled the site of Sebastopol at Woolshed Creek. William Cross Yuille was just 18 years of age and his cousin Archie about the same age. What they thought of this great seemingly empty land is not recorded. However life must have been difficult for these young men. Henry Anderson, also a young man, and the Yuilles parted company soon after arriving and W.C.Yuille moved closer to fresh water on the southern shores of Black Swamp. Anderson settled 5 miles south of Ballarat at Cambrian Hill and Archie Yuille remained at the original site at the junction of the Yarrowee and Woolshed Creek. In 1840 Archie commenced building a house, the sandstone foundations of which were used to build a memorial cairn at the end of present day Bala Street, Sebastopol. Withers in his book “A History of Ballarat” states that the house was, other than the foundations, never built. Probably because the Yuilles left the district before they had time to complete it.

William Cross Yuille gave Black Swamp his name for a number of years. If he built a house on the shores of the swamp no trace of it remains today. However a monument was erected at the end of Pleasant Street just across from Pleasant Street School on what was supposed to have been the site of his first camp. It was erected in 1934 some 90 years after Yuille arrived. Yuille was the first European to bring change to the Swamp. The other pastoralist who took up a run on the north of the swamp was Waldie who settled about 3 miles north of the Swamp near the present line of Gillies Street.

In 1847 the population was still sparsely scattered through the district with Buninyong the main town of any size. A wagon road, first blazed by Anderson and Yuille, ran from Buninyong through Albert Street, Sebastopol into Skipton Street, Armstrong Street then swung northwest up the rising ground into Creswick Road following roughly the course of the Yarrowee Creek. Then following Gnarr Creek it skirted the Old Cemetery into Burnbank Street and then to the shores of the Swamp where the Gnarr flowed into the Swamp and where bullock teamsters had a campsite. Camping there they would then continue out to the Pyrenees range and Clunes. Arthur Jenkins in his book “The Golden Chain” states that this track would be amongst the oldest roads in the colony. Even when the township of Ballarat was properly surveyed and set out in a regular grid pattern this route was adapted into the present day road system with only minor deviations.

The pastoral idyll lasted a little more than a decade. In that time most of the colony inland was settled by pastoralists taking up huge tracts of land from here to the South Australian border.

The Goldrushes 1851-1860

Then on July 29th, 1851, Charles Esmond discovered gold at Clunes. This was followed quickly by Hiscock's discovery at the gully that now bears his name near Buninyong on August 8th, 1851. With the discovery of gold came a tidal wave of humanity all bent on making a quick fortune. Their arrival shattered forever of the tranquil idyll - the pastoral peace. Caught up in the lust for gold, the miners, who flocked to Ballarat, paid scant heed to the beauty of their environment. All was pushed aside and torn asunder. Not since Mt. Warrenheip last erupted had the environment suffered such catastrophic upheaval. The shady trees were cut down and used for firewood, shelters and mining activities. The limpid pools and gentle streams were diverted, re-routed and sullied with the clay washed into them in the frenetic search for the gleaming metal. The clay subsoil was all turned up to the surface and exposed to sunlight and with rain became alternately dust, quagmire or concrete.

In 1852 the Swamp that had been such a peaceful resting place was now “employed” to provide clean drinking water for the rapidly growing populace. The first attempt at reserving water for the township was made by building a small dam across Gnarr Creek to intercept the overflow from the Swamp. This however proved unsatisfactory. The oasis, for a time, became simply a muddy waterhole in the midst of desolation. Denuded of the golden wattles, scattered gums and drooping she-oaks, its beauty secondary to the utilitarian purpose of supporting life on the goldfields. Mining activities spread over the Ballarat flat like a cancer right to the very shores of the Swamp itself. Mining in this area was still sparse as the Swamp was a good 2 miles from Main Road and the main areas of settlement in Ballarat East. As the township grew and spread, the importance of a good source of water increased. The many creeks and streams had been degraded to such an extent that they were little more than open drains. The water supply from the Swamp grew increasingly important in Ballarat’s ongoing survival. The forest reservoirs too played an important part-the Gong, Kirk’s, Beale’s and Pincott’s. But being further out of town these man made reservoirs did not possess the natural charm and beauty that excited the imagination and caught the attention of the early pioneers.

In 1854 Rowland and Lewis established their aerated waters factory on the east shore of the Swamp near the present day site of Nazareth House. The paddock adjacent became known as the Lemonade Paddock. They operated there for years supplying safe bottled drinking water to the populace. Several other businesses also built along the shore; Courtney’s Flour Mill near present day Mill Street, Fry’s Flour Mill on the corner of Ripon Street and Wendouree Parade and Duncan’s Nursery somewhere near where the Gnarr Creek entered the Swamp. The District Surveyor’s Office was also located about where the lake Kiosk is today.

In 1855 the district of Ballarat was constituted a municipality on the 17th of December. It was also in this year that Wendouree Parade was first surveyed. In 1856 a small dam was erected at the outlet of Yuille’s Swamp to reserve additional water for the summer months. The City Council made an application for a loan or a grant to reserve a road right around the Swamp and also planned to bring water from the swamp to the township by means of iron pipes.

On October 24th by-law No.7 was gazetted giving the Municipal Council of Ballarat exclusive rights to the Swamp. In 1856 Henry Richards Caselli who had been in Ballarat for a year, demonstrated his civil mindedness and considerable engineering skill and expertise, by suggesting that earthenware pipes should be used rather than iron as they could be made locally, would not rust and would not delay the project as the state of the road from Geelong was delaying the delivery of the cast iron pipes. It is great pity that the Council did not take his advice, as the cast iron pipes laid over a hundred years ago will continue to need replacing. Henry Richards Caselli however would go on to achieve even greater things making a contribution to Ballarat and leaving a legacy that has no equal.

In 1858 the Municipal councils of East and West met to discuss a joint water supply from Yuille’s Swamp. There was considered to be insufficient water to supply both municipalities so the Western Council declined to enter an agreement. This same year 102 acres of flat bushland to the west of the Swamp that had previously been the police paddock was gazetted for botanical gardens.

The pipeline first mooted in 1855 was finally completed to convey water from the Swamp to the township. Filter beds approximately 50 foot wide and 30 foot deep were located on the edge of the Swamp opposite Webster Street . A cast iron, 9 inch pipe was laid down Webster Street underground to corner of Sturt and Lydiard Street and Sturt and Lyons Street where standpipes were located. From these standpipes, carters would fill their wagons with filtered swamp water and sell it all over the goldfields. The crown shaped scoria fountain at the Webster Street end of the Lake was constructed in 1879 to mark the position of the old filter beds. It was later improved in 1901 - two stone arches were added and several beds formed around the base and planted with cordylines, yuccas and aloes – the remnant planting is still there today.

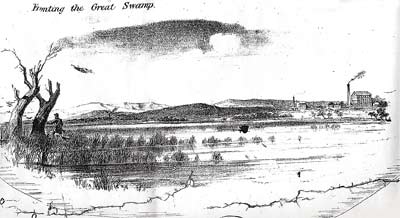

This lithograph shows the unformed edges of the Swamp in about 1859 or 60 just near a building that is probably Baird and McPhillimy’s(later Brown’s) Mill. It is really a long way out of town and only one or two houses are visible. The vegetation is remnant eucalypts with no planting or “civilising” of the Swamp at this time.

View near the Swamp-Cogne 1859.

Lithograph 275x437mm. Collection:Ballarat Fine Art Gallery. Purchased 1974. Courtesy Ballarat Fine Art Gallery.

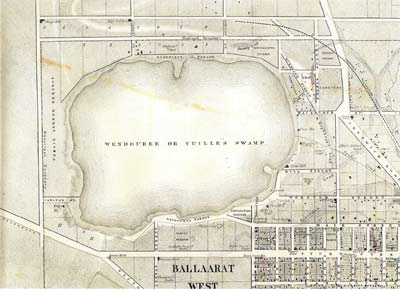

Map of the Swamp, 1861.

Wendouree Parade still does not extend right around the swamp, no boatsheds are in evidence but Brown’s Mill and the Wheatsheaf Hotel and several other landmarks can be distinguished. Note the rectangular filter beds clearly shown just across from the end of Webster Street.

(Courtesy Department of Natural Resources).

Civilization

After the initial frenzy of the gold rush, life in Ballarat in the 1860’s began to take on a much more ordered and civilized air. Many of the miners who had come early seeking their fortune in gold realised that fortunes were ready to be made in other areas - commerce in particular. These men began to put in place the infrastructure that would ensure Ballarat’s survival and growth well into the future.

Prior to 1861, Ballarat East was the main focus of mining and commerce but from 1861 onward the “boom in the west” meant that the area between Lydiard Street and the “Swamp” became more and more urbanised. In the 1850’s Main Road was just that, the main artery supplying the heart of Ballarat with goods and people entering the township.

In April 1862 the railway was opened and now, instead of entering via Main Road, passengers and goods would disembark at the railway station in Lydiard Street. And so it followed that they would seek accommodation closest to the transport. Lydiard Street still has the fine hostelries that welcomed those guests - Craig’s Hotel, the Provincial and The George. For goods arriving by rail, the Haymarket developed just a short walk from the station. Most of the city west of Lydiard Street was built in the decade 1860-1870-shops, houses, and manufactories in possibly the greatest building boom Ballarat has seen. A prime example of this is the Mitchell Building (now Myers) which was started in 1869 and built at a cost of 10,000 pounds. It was designed by noted architect Henry Richards Caselli and had one of the first cast-iron verandas for which Ballarat became renowned. It is an outstanding example of the solidness and sturdiness of the “new” Ballarat.

Suburbia crept slowly but surely closer to the Swamp and its proximity led to the citizenry embarking on recreational pursuits. Even in these early days “Around the Swamp” was a favourite Sunday walk according to the Mayor’s Special report of 1881. Although Urquhart in his survey of 1858 had called it Lake Wendouree it had none of the features that would truly distinguish it as a lake. Land had been reserved on the western shores of the Swamp in 1858 for the Botanical Gardens. This again lent further attractiveness to the area. But “Swamp” it still very much was, being covered in thick dense green rushes probably four to five feet tall. There was only a small proportion of cleared area and that basically around the edges for about 10 yards (metres) or so depending on the water level. There was most certainly no clear water for sailing or rowing. The edges would have been soft, squelchy mud-very much au naturel as no work was done on the surroundings for several more years.

In 1860 an underground pipeline from Kirk’s Reservoir was run to the Swamp in order to top up the water levels particularly in summer. In a rare display of co-operation East and West councils cut several miles of drains for conveying storm water into the Swamp. The filter beds were also improved and the swamp reserve fenced to stop cattle wandering in and polluting the water. The Saxon Mine began operation at the top end of Pleasant Street on the site of the current City Oval.

On October 10th 1861 one Robinson (Bob) McClaren, of Ballarat, journeyed to Melbourne to take part in a sculling match against Prescott of Richmond. Bob McClaren had rowed in England as a member of the Thames and Tay clubs in England and the Yarra Club in Melbourne. He won the trophy valued at 10 pounds and returned to Ballarat determined to see the sport of rowing established here. McClaren owned a hotel and sporting saloon in Main Road and later Bridge Street. Colonial artist S. T. Gill did several sketches of the somewhat infamous McClaren’s establishment. Bob McClaren was a sporting entrepreneur and adventurer- a man ahead of his time. It was principally he that was the inspiration and the driving force behind the beginning of rowing in the Ballarat District.

Not being one to let grass grow under his feet less than a month later, on November 18th 1861 Bob called a meeting of rowing men to see about the possibility of arranging Ballarat and District Regatta at Lake Burrumbeet. The meeting of Messrs. Kerr, W. Craig and Robinson McClaren started raising subscriptions for the regatta. The Star newspaper reported that this was in fact the second regatta in the district, alluding to one held a few years earlier although not very successfully. The “Swamp” wasn’t even considered as a possible venue at this time. Bell’s Life in Victoria and Sporting Chronicle printed the following article regarding the commencement of rowing in Ballarat.

“The victory of a Ballaaratian over a sculler of Melbourne, in a recent rowing match on the Upper Yarra has given impetus to aquatic sports on the “metropolitan goldfield. “It has for years been regreted that many on Ballarat who are inclined to indulge in rowing exercises have never hitherto had an opportunity of indulging their propensities. This want is, however, now likely to be supplied; for a meeting of those interested in the movement will be held on Wednesday next at 7 o’clock for the purpose of initiating a Lake Burrumbeet regatta. The difficulty which was formerly experienced in getting a proper class of boats is now obviated and the affair has been taken in hand by those who have both the judgement and the means necessary to carry it out.”

(Saturday, November 16th 1861, Bell’s Life in Victoria and Sporting Chronicle)

Mention was made of an earlier regatta that was held in the district, although not very successfully. This may refer to the Ballarat Typographical Association Annual festival at Lake Burrumbeet in November 1859 where there was some boating activities but no great skill displayed.

Further improvements were made to the swamp this year with more storm water drains cut on the north side of the swamp and an agreement was struck with the few private landowners in the vicinity to purchase the land necessary so that water could be gathered and diverted into the basin from a greater area including from the “Little Swamp” to the west of the main swamp.

Picture of the Swamp from an early Land Sale poster circa 1863 Courtesy Ian Atkins, Ballarat City Archives.

1862

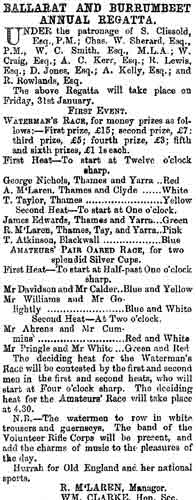

So it was on the Friday, 31st of January 1862 the very first Ballarat District Regatta was held at Lake Burrumbeet.

And what an amazing achievement and spectacle it was. Boats had to be borrowed from Melbourne and were brought up to Ballarat by German wagon along Plank (Main) Road on the 25th of January 1862 where they remained overnight. The next morning, festooned with flags and greenery, they were taken out to Lake Burrumbeet. At this point there were only three four oared gigs (boats) in the whole of the Port Phillip District so all the races were in pairs and sculls. The populace of the township were granted a public holiday in order to enjoy the event and every conveyance available seemed to make its way out of town towards the shores of Burrumbeet. Some 5,000 spectators were reported to have been in attendance.

Advertisements were placed in the Star newspaper and show the profound influence English rowing had on the beginnings of rowing in the colony.

After the regatta a copious report of this unique event was published in the Star on the following Saturday February 1st, 1862.

Advertisement from the Star newspaper Thursday, January 30th, 1862

Part of the report from the Star newspaper, Saturday, February 1st, 1862

After the huge success of the regatta, the committee met again on the 14th of February 1862 and officially constituted the Regatta Club drawing up rules and accepting the nominations of twenty-two new members. Two boats were purchased in late February and in April the club held pair -oared races, again at Burrumbeet. The next Ballarat and District Regatta was planned for November 28th, 1862 but this was postponed due to tragic circumstances.

Mr. J. R. Pringle, a vice-president of the Regatta Club, was drowned while training on Burrumbeet on November 18th, 1862. In most histories that is all the mention James Pringle receives, but his story is rather tragic and because of the impact his unfortunate demise had on the destiny of rowing in the district, I will fill in the details.

James Pringle and Alf McClaren (younger brother of Bob McClaren) had gone out for a training row on November 18th when their boat was overturned by a squall. Both men clung to the upturned boat. Despite McClaren being a capable swimmer he stayed with his training partner and friend until James could no longer hang on and slipped under the water. Mr Dobson, of the Picnic Hotel, had seen the men go out and was alarmed by the length of their absence. He went out to look for them and found Alf in a pitiable state. Of Mr Pringle there was no sign. Mr Dobson rescued Alf McClaren conveying him back to shore. But the rescue came too late for James Pringle. His body was not recovered for another seven days despite extensive searches and dragging of the lake with heavy boats brought up from Geelong by train. Mr Pringle had formerly been a member of the Regatta Club at Newcastle on Tyne in England. All his friends assumed that he was a proficient swimmer. Tragic enough as it was, this event was made even more tragic by the fact that Pringle’s only brother also drowned years earlier being lost overboard in a shipping accident. Mr Pringle’s funeral was a grand and sombre occasion with some 3,000 people lining the way and attending the burial. He had been a member of the newly formed Ballarat Troop of the Victorian Lighthorse Regiment. His funeral was the first occasion that the Ballarat Troop provided a full military display of any sort in Ballarat. He was buried with full military honours in the Ballarat General Cemetery. Mr Pringle’s horse was led in the procession with his boots placed in the stirrups backwards. Some 3000 people watched the procession and many followed it to the cemetery.

There is a poignant postscript included at the end of the funeral report in the Star, Wednesday, November 26th.

“A pleasing little circumstance has come to our knowledge in connection with the decease of Mr Pringle which will tend to show how widespread was the esteem to which his good qualities gave rise. His housekeeper, a lady of advanced years, sought and obtained from the immediate friends of the deceased gentleman the privilege, as she demanded it, of keeping watch over the body during the last night that it was to remain above ground. Mr Morris, in whose charge the body was placed overnight, permitted the good lady to have her wish; but previous to his retiring to rest she gave him many instances of consideration and generosity on the part of the deceased, whom she stated to have acted a truly filial part towards her. In the morning, Mr Morris found the old lady seated by the side of the coffin, the top of which she had strewn with flowers.”

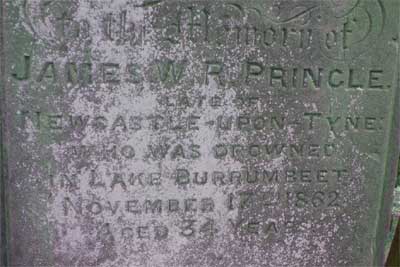

His headstone is located in the Old Cemetery just alongside the Eureka memorial for the soldiers killed in that affair.

Mr Pringle's headstone

The inscription reads: Sacred to the Memory of James W.R.Pringle, late of Newcastle-Upon-Tyne who was drowned in Lake Burrumbeet November 17th, 1862, Aged 34 years.

This year the Swamp became inadequate to supply water for the growing population of some 20,000.The Municipal Councils of East and West received a grant of 10,000 pounds to buy Kirk’s Dam to supply water to the whole district. Bluestone quarries were established on the shores of the swamp at the present day View Point and St Pat’s Point. Bluestone for many of Ballarat’s constructions projects and buildings was taken from here.