1919 Peace Regatta—and other Inter-Allied Armies Regattas after WWI

Inter-Allied Rowing

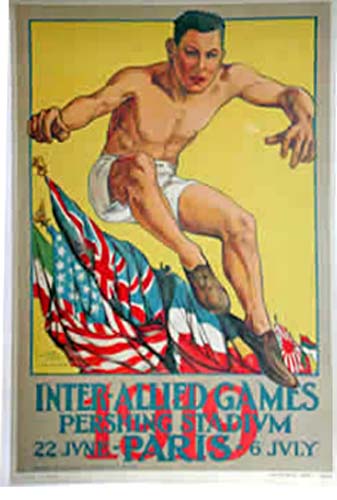

While the crews were training for the blue-riband event at Henley, the representatives of the American Army who had promoted the big Inter-Allied Games in Paris made every endeavour to induce the Service crews to take part in the Rowing Section of their Games. In order to fit in with their programme and not to clash in any way with the Henley event, the Inter-Allied Regatta was fixed for July 17th and 18th. This gave the crew twelve days in which to get their boats across to the Seine and settle down in new quarters.

Very complete arrangements had been made by Lieut.-Col. David M. Goodrich, Vice-Chairman of the Inter-Allied Games Committee, a Staff Officer of the U.S. Army, for the transport of the boats and crews. Lieut.-Col. Goodrich was a very prominent oarsman of Harvard University, and he accomplished great things in connection with this regatta. The Service crews' boats were taken by motor-lorries to Southampton, and there placed on board an American destroyer and taken to Le Havre, to be again placed on lorries and taken to Paris. Unfortunately, delay occurred in the last stage of the journey, and the boats only arrived in Paris three days before the race.

The course selected was on the Seine between the Pont de St. Cloud and the Pont de Suresnes, a distance of about 1 mile 330 yards, close to Paris. There was a good stretch of water and plenty of room for three crews to row abreast, the race being rowed with a slight current. All arrangements for the housing of crews and boats were excellent, large aeroplane tents having been specially fitted up for the shells. It was rather unique in the annals of sport to see athletes from all the Allied nations messing together in one large hut. The feeding arrangements were also first-class, and the whole show was a striking example of American organisation and attention to detail.

The programme of races consisted of eights, fours (with coxwains) and sculls. The Australian Army entered a sculler and an eight. Unlike Henley, the regatta was a purely Service event, and professional athletes were allowed to compete with amateurs. The entries for the eight-oar race consisted of crews from Czechoslovakia, Italy, Belgium, Australia, New Zealand, United States, Canada, Portugal, France, with Cambridge University as the representative of England.

Canada, Belgium, Italy, France, New Zealand, Portugal, and the United States entered fours, and Cambridge University, United States, New Zealand, Australia, France, Italy, and Belgium sent scullers.

The racing did not attract a great number of Parisians to the river bank, but the regatta, being an Army concern, and in no way a money-making venture, was not advertised. Rowing is not a very popular sport in France, being confined to a few enthusiasts. In any other country where rowing had a vogue, such a remarkably cosmopolitan meeting would have drawn thousands to the river. In this particular case the racing provided would have amply repaid them.

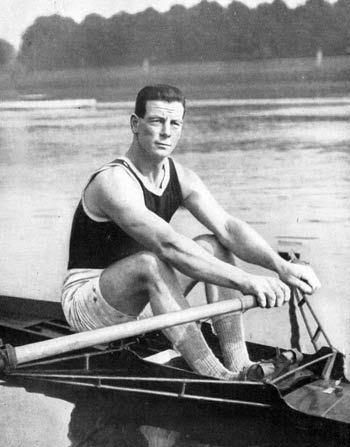

Alf Felton who later won the World and English Sculling Championships on 27 October 1919

The Single Sculls Race held a good deal of interest by reason of the fact that Hadfield the New Zealand amateur who won at Henley, was to be opposed by A. D. Felton, the Australian professional, among others. There had been a good deal of rumour regarding Hadfield's intention to turn professional to row Barry for the world's championship. Although many good judges fancied Hadfield's chance of success in the professional sphere, it must be stated that the New Zealander never contemplated the change. The race between Hadfield and Felton was early robbed of its interest by Felton striking a buoy marking the course. He damaged his boat and had to retire. Hadfield won this heat and subsequently won the final by a comfortable margin.

The rowing in the four-oared race was not of the highest standard. The French crew did well to win from the United States crews, whose performances at Henley had been rather good.

The great interest of the regatta centred in the eight-oar race, The English-speaking crews and the Frenchmen had already met at Henley, and had learned to respect one another. The Australian crew had altered very considerably since its win at Henley. Middleton and Hauenstein, the two Olympic oarsmen, who had supplied weight and experience, were not available, and the result was that four alterations had to be made in the boating, two new men being brought in from No. 2 Crew.

This was unfortunate, but would not have been so bad had the new crew had an opportunity of getting together. As it happened, there was no boat available after Henley Regatta, one having been sent back to the owners and the other to Paris. Then the late arrival of the boats from Le Havre added to the trouble. The crew had not been afloat for eight or nine days, and had two and a half days in which to learn the course and get into their swing.

The boating of the A.I.F. crew for this race was as follows:

Sergt. A. R. Robb (bow), Lieut. H. R. Newall (2), Lieut. L. S. Davis (3), Gunner A. V. Scott (4), Lieut.

T. McGill (5), Lieut. F. A. House (6), Gunner G. A. Mettam (7), Capt. H. C. Disher (stroke). and Sergt.

A. E. Smedley (cox.).

The French crew had not done themselves justice at Henley, being seriously handicapped by their late arrival on the river and by having to row in strange boats. Of the Continental eights, those from Portugal and Czechoslovakia did not appear to be likely to be troublesome. The Italians and Belgians were reported to be fast crews, but results showed that the Belgians were not nearly up to their usual high pre-war Henley standard. The Italians also had not the pace for the company in which they found themselves.

The race was rowed in three heats, the winners contesting the final. The Australians were drawn in the first heat against the Czechoslovaks and Italians, and the crews finished in the order named after a rather tame race, in which the winners were never extended. Time 6mins. 48 2/5secs.

New Zealand, Canada, Belgium, and Portugal lined up for the second heat. The result was not long in doubt, for the New Zealanders established a lead early in the race, and drew away to win comfortably from the Canadians, who rowed gamely, but never looked like being the winners. Belgium was third and Portugal last. Time 6mins. 37secs.

New Zealand Army Eight who competed in the Final at the Pershing Games Paris 1919.

The third heat saw Cambridge, United States, and France facing the starter. This was the most exciting of the heats, and was a magnificent struggle all the way between Cambridge and America. The University crew won by half a length in 6mins. 35secs. The French crew had already been beaten by the Americans at Henley, and again found that their pace was not fast enough to keep up with the U.S. crew.

The final was rowed an the following day, July 18th and those who predicted a great struggle between the three British crews were not disappointed. The race was held under perfect rowing conditions—smooth water and no wind. The Australians drew the central position, but there was no advantage in any of the stations, and plenty of elbow-room for all three crews.

Lieut.-Col. Goodrich, who had performed the arduous duties of starter and umpire for all the events of the regatta (no sinecure, where it was necessary to carry an army of interpreters on the umpire's launch), got the three crews away to a wonderfully even start. Cambridge went off at a tremendous rate of striking for the first thirty strokes in an endeavour to gain a lead. When the crews settled down Cambridge had a slight lead from Australia, with New Zealand dropping back.

They rowed in this order to the half-way mark, where from the umpire's launch it was impossible to say which of the two crews led. If the Australians were in front at any time during the race it was at this point. The New Zealanders had fallen away gradually, and it was evident that they would take no part in the tremendous struggle which was developing. It was also apparent that the crew which could muster the better final effort would get the victory. The two boats came dangerously close together, and the umpire warned the coxswains to pull out in order to avoid a foul. Over the second half of the course the crews rowed practically stroke for stroke — desperately hard, but good form and high-class rowing. Cambridge undoubtedly led by a few feet in the rush into the straight, and, by a magnificent effort at the finish, raced across the line winners of a superb race by a third of a length. The New Zealanders were about a length behind the Australians. Time, 6min. 26 3/5 secs.

There was terrific excitement among the spectators in the reserve on the shaded bank of the river at the finish. Although the A.I.F. men were beaten, their performance under many difficulties rather enhanced than lowered their reputations as oarsmen. They were a very popular crew among the many assembled at the camp.

At Henley, the home of rowing, one expects to find perfection in the regatta arrangements, and the experience of many years has produced the very best. On an occasion such as the Inter-Allied meeting, one is prepared to put up with many little inconveniences. It was surprising to find, therefore, that the arrangements were such that everybody was comfortable and contented.

The crews started from moored boats. The course was buoyed off. Spans of bridges were numbered. A telephone was established between the starter and judge. Results were signalled by bombs and flags from the bridges. The whole arrangements for the comfort of the competitors and visitors left nothing to be desired. All this had been done at short notice, and done very well indeed.

This regatta marked the end of the A.I.F. rowing, there being no further races of an international character. The personnel left for Australia by the steamer "Euripides" on September 6th.

AIF No 2 Crew in South Africa on way home to Australia