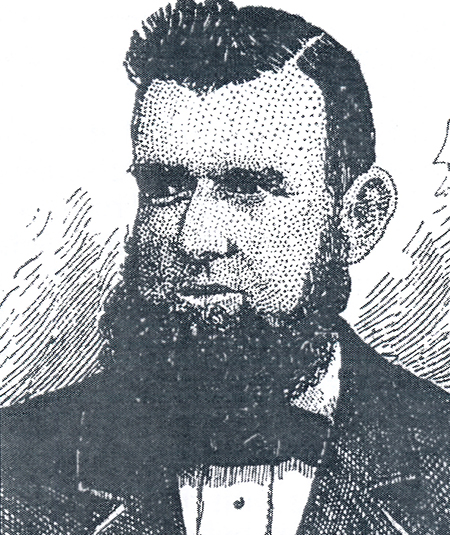

William Hickey

Professional Sculler from Newcastle

William Hickey (c1844-1891) was Australia's top rower in an earlier era. William was widely regarded by many as superior to any other rower produced by Australia during the latter half of the 19th century; a list that includes world champions such as Trickett, Beach, Kemp and Searle. Certainly, he ranks with the nation's greatest.

As with his younger brother Richard, William developed his skill delivering milk by rowboat twice each day from Dempsey Island to Newcastle. Almost invincible in the Hunter, William, made his Sydney debut on Port Jackson at the Anniversary Regatta in 1865 winning a race in light skiffs. Later, as a farmer and little known in Sydney rowing circles and therefore not highly rated, he defeated Richard Green in June 1865 in a licensed waterman boat for a £170 stake to become the Australian champion rower in watermens skiffs. Within days, as a tribute to his win and the honour it reflected on Newcastle, his supporters gave him an outrigger wager boat named "Rose of Australia". Thirty three feet six inches long and weighing 40 pounds (lbs) (35 lbs without riggers), it was described as a "beautiful specimen of its class".

However, to be the Australian sculling champion he had to beat Green in best boats (racing sculls). He did that in January 1866 on the Parramatta River in wager boats for a stake of £200. It was just his second race in a light outrigger skiff. (Note the various terms that could be applied to the same boat). The records are contradictory but it seems most likely that he held the championship until defeated by Michael Rush in December 1870.

William effected what was regarded, even 50 years after the event, as the most remarkable race ever over the championship course on Parramatta River. In December 1865 he rowed Harry White, the crack English rower, in wager boats for £100 a side. Although Hickey was 6 to 4 on favourite, White's imposing record meant that he had many supporters. Briefly, both rowers got away together with Hickey taking a slight early lead. Both boats were together for a mile when the race unfolded like the script of a theatrical drama. Off Kissing Point, Hickey fouled a moored boat giving White a long lead. When Hickey got into his stroke again spectators were treated to one of the best if not the greatest feat of sculling ever witnessed on the river.

William Hickey

Rowing in great style, he bent to his work and at two and a half miles had reduced White's lead to just half a length. "Could Hickey last?" was the question as the excited onlookers cheered on their favourite. At the Point, Hickey slipped up on the inside and in just a few lengths forged into the lead. From then on he had it all his own way and at the winning post (The Brothers) was a good three lengths ahead, winning in 24 minutes 50 seconds. Subsequently, William was described as " ... a most extraordinary puller. He has wonderful strength and activity with indomitable pluck. His feat (winning the race) was of no ordinary character".

Stake money for his rematch with Green in 1867 was £200 a side. For one of his contests in heavy boats against arch-rival Rush in 1870 stake money was £500 (almost certainly £250 each), He lost his Australian title to Rush later the same year when the stake was £200. Even so, Hickey's confidence was such that in 1871 he announced himself as "Champion of Port Jackson" and open to row any man in Australia in any class of boat for £100 or more.

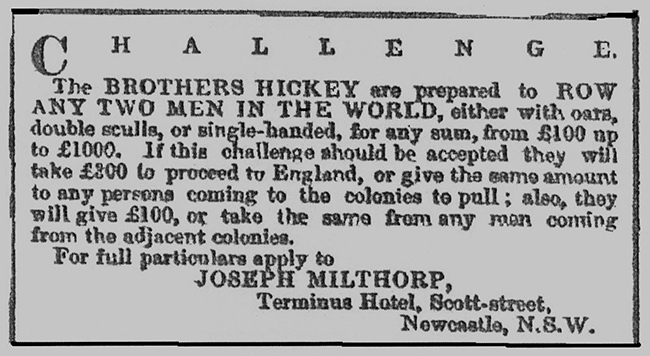

Regarded locally as unbeatable when either rowing or sculling together, in 1869 the two brothers issued what is possibly the most famous challenge in Australian rowing.

Such a challenge was audacious in its scope - anyone, anywhere, in singles, doubles or pairs. With no championship involved, the stakes, for the time, were enormous.

Later, James Renforth the English and world sculling champion offered to row William on the Thames or Tyne for the world championship and £1000 a side. Naturally, this caused great excitement in Newcastle, ours, that is, not theirs for, coincidentally, Renforth was from Newcastle too -but the English one. Even with assistance from a local committee formed for the purpose and the opening of public subscriptions, the estimated £1200 necessary could not be raised so the challenge lapsed. We will never know how he would have fared but he was considered by many knowledgeable judges who were familiar with the champion rowers of the day including Canadian Edward Hanlon (world champion 1880-84) that William was the "best man we ever had and perhaps the best man that ever sat in a boat".

Whilst William Hickey's record was as a sculler in light skiffs was impressive many of his contemporaries believed he was even better in the "good old days" of heavy boats with fixed seats. These required great strength to row: skill was secondary. In a race between Hickey and Rush in 1870, the farmer's boat was 33 ft long and 4'10" wide; the latter's 34' long and 5'2" wide. When one considers that 22' skiffs were usually used for as singles and doubles, racing such large boats had to be hard work. Obviously, whoever called them the "good old days" had never rowed one.

Colin Charters

Extracted from his book Just Add Water - the Times an Tides of Newcastle Rowing Club, published by Seaview Press 2009