Sydney Rows

A Centennial History of the Sydney Rowing Club, 1970, by A L May

Table of Contents

Chapters

- Preliminaries: before 1870

- Foundations: 1870-1880

- New Clubs: 1880-1890

- The Amateur Question: 1890-1900

- Sydney on Top: 1900-1910

- Henley and War: 1910-1920

- Pearce and Mosman: 1920-1930

- Financial Problems: 1930-1940

- War and Wood: 1940-1950

- Strength and Stability: 1950-1960

- On Top Again: 1960-1970

Appendices

3. New Clubs: 1880-1890

The fate of the intercolonial eights was now in the balance as far as NSW was concerned - unless some colonies, or sections thereof, agreed to meet NSW under the old definition. Upward was soon heading moves in Victoria among the bona fide amateur clubs to form a new Association to carry on the old series of races.

The Victorian clubs concerned drew closer together and conducted a regatta among themselves. The VRA itself declined to continue the intercolonial eights on other than the new terms, but appeared amenable to granting its patronage to any other group which wanted to conduct a race on the old terms. For its part, it decided to open its champion four and champion scull events to the other colonies (Queensland being the only one to take advantage of this position).

In September 1889, the NSWRA received a letter from Upward on behalf of Victorian amateurs (principally from Melbourne, Banks, Mercantile, University, Civil Service and Electric Telegraph) suggesting a continuation of the event under the old definition and the Association agreed to send a crew to Melbourne for a special regatta in November. The National or Anniversary Regatta in Sydney in January 1889 had been marked by a good win to Mercantile over Sydney in the senior fours, although Gerald Kennedy doubled up to take the Laidley Sculls. The Association conducted a special senior eight race in April, presumably to fill the gap caused by the ending of the April intercolonial.

Five crews entered, with Sydney, rowing in a new eight by Edwards of Melbourne, being out rowed by Mercantile. The latter had, however, fouled East Sydney earlier in the race and was disqualified. Sydney declined to accept the prizes, while Mercantile bitterly disputed the action and announced the club would not again start in races under the control of the same umpire - F. J. Smith, M.L.A., honorary secretary of the NSWRA!

A further senior eight race was conducted by the Association in August, and this time Mercantile, coxed and coached by John Blackman, won again. Sydney failed to last the distance and finished only fourth, behind Glebe and East Sydney. John Blackman was given the job of selecting the intercolonial eight, but several oarsmen, including Ted Kennedy, Johnson and Payne of Sydney, declined to accept seats. Gerald Kennedy later dropped out through illness, leaving Stewart Tiley Sydney's only representative in the crew.

There were five from Mercantile (including Nathaniel McDonald and John Thomson, formerly of Sydney), a Glebe man and one from East Sydney. Victoria started warm favourites for the race itself and, it proved, with good reason. The Vics got away soon after the start and gradually drew away to record a 3 length win.

There was some excitement still left in the decade. A special maiden eight race was staged by the Association at the end of 1889, with Sydney finishing second to East Sydney. The RA also determined to hold a four-oared race in best boats in May, 1890, open to all clubs in all colonies. The race drew criticism, as only one or two Sydney clubs had best fours. The race was won by the one visiting crew - Breakfast Creek of Queensland-by a good margin from Mercantile with Balmain third. Gerald Kennedy had an easy win in the Sydney Mail Challenge Cup sculling event held on the same day.

Attention also focussed on St. Ignatius', firstly because of its challenge to Geelong Grammar School, the Victorian champions, to a match. The race took place on the Barwon River in 1888 with Geelong winning by 3 lengths. A return race was rowed on the Lane Cove twelve months later and, this time, St. Ignatius' was successful.

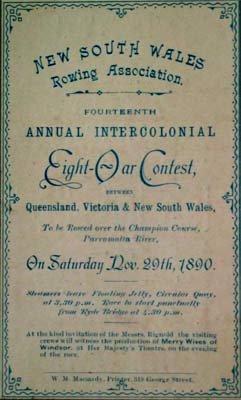

1890 Intercolonial Regatta Programme Cover

Efforts to interest more Sydney schools in rowing were made by the Association, as St. Ignatius' was the only school active at the end of the decade. The college's regatta also attracted additional interest when it became known that the committee concerned was seeking funds for a grand challenge cup for the senior eight event to be rowed for annually. The race was conducted at the June, 1890 regatta, being called the Lane Cove Challenge Eights. Mercantile took the event with Sydney setting the example for many future crews by hitting a pile near the finish when in a handy position.

Other Developments

A number of matters related to the internal workings of the NSWRA are of interest. At the commencement of the decade, there was some want of unanimity between the Association and the clubs arising through the rule that "only members of the Association are eligible to compete in any of the races held under its auspices". A meeting in August, 1880, altered the rule so that members of any subscribing club (the fee being £5/5/0) became eligible to compete at any race if nominated by their club on payment of a fee of 5/-.

The Association's annual meeting at the end of 1881 brought to light some of the frustration felt by its officials. The honorary secretary, Henry Coles, announced that, after reflection, he felt "so dissatisfied and disgusted with last year's results as to almost induce him to take no further interest in rowing". Many members of the committee were, he said, apathetic. And the honorary treasurer endorsed all the secretary's remarks. Finances were a continuing problem.

An Association meeting in June, 1884 disclosed "a very woeful state of the finances" due to the heavy expenses involved in the intercolonial event. The Association financed part of its activity by overdraft but in 1888, the year of strife with the elected treasurer, a deficiency of ₤324 was realised for the year and a subscription list was opened to attempt to overcome the difficulties.

Apathy of members to the Association gained special reference from the chairman, George Thornton, at the annual meeting of January, 1885, which was very poorly attended. There was a poor attendance again in 1886 and the 1887 meeting was postponed due to lack of a quorum. Three attempts were needed before the 1890 meeting was finally held. Early in 1889, one writer was describing the Association as being deep in debt and "almost dead". He called for a radical change in the management of its affairs. Early in 1890, a subcommittee was appointed to revise its rules.

On minor item coming before the Association deserves attention. In 1889, it was alleged that William Goulding of the East Sydney Club had rowed for a money prize and was not a bona fide amateur. Accordingly, the eight in which he had rowed should, it was said, be disqualified. It transpired, however, that East Sydney had realized the position and had withdrawn Goulding from the crew concerned before the race, so the protest failed. A month later, Goulding was recognized by the Association as a bona fide amateur, going on to considerable success and, later, to introduce his two sons, Bert and Jack, to the sport of rowing.

Professional sculling continued to attract a large following. Amateur oarsmen and rowing officials were, indeed, amongst the keenest supporters. In 1880, Ned Trickett was champion of the world, but was being challenged by Edward Hanlan, the Canadian. A match was finally arranged on the Thames in November, 1880, for the championship and ₤1000 a side. Hanlan took the title from Trickett and later defeated Laycock, also on the Thames.

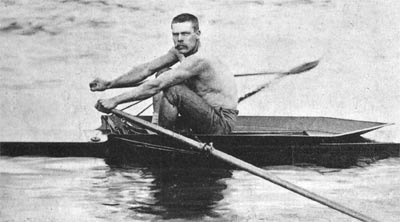

Bill Beach

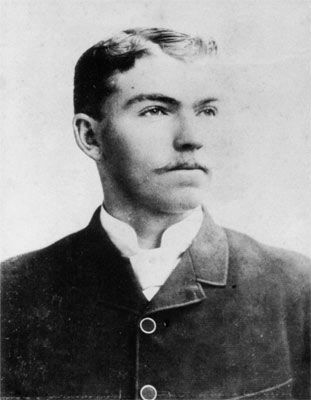

Back in Australia, nurtured by the keen interest and the big betting involved, a new champion, Bill Beach, was emerging. In 1884, Hanlan visited Australia to race him for the title and £1000 a side. Beach, a blacksmith, won easily before a vast crowd, and he went on to retain his title in six more races over the next three years, both at home and in England. Finally, he was challenged by Peter Kemp, from the Hawkesbury River, and he decided to retire and to forfeit the title to the challenger. Kemp held the title in three matches, including two wins over Hanlan in Sydney. He yielded it finally to the young Henry Searle, from the Clarence River. Searle retained the title in England against O'Connor of Canada but, while returning home, fell victim to typhoid fever. He died in 1889, aged only 23. A monument to the memory of this very popular champion sculler was erected two years later at The Brothers on the Parramatta River, the finishing point of the championship course.

According to `Banjo' Paterson, the Hanlan-Beach matches started "such an orgy sculling as never was seen in the world before".

He goes on:

"From twenty-five to thirty men could be seen on any fine morning (on the Parramatta) swinging

along in their sculls at practice - and such men! From riverside farms, from axemen's camps in the North

Coast timber country, from shipyards and fishing fleets, they flocked to the old river as the gladiators

flocked to Rome in the last days of the Empire. Hanlan, who had toughened himself by work as a fisherman,

Maclean, an axeman, who could fell any tree, using an axe in either hand, and never resting till the tree

came down; Searle, who as a youngster rowed a boat about the Clarence River, taking orders for and delivering

meat on account of a local butcher - he too was caught up in the renaissance of rowing, and found himself

translated from the butcher's boat to the championship of the world...

Henry Searle

"On the death of Searle, the championship was claimed by Maclean and Stanbury of Australia and O'Connor of America; but after the renaissance came the decline; apart from the general disinclination to bet on anything that could speak, the expenses killed the business. The only gate - money that could be got was a percentage from the river steamers, and it cost five hundred pounds to boat and train a man properly in a match for two hundred pounds a side. So the glamour of professional rowing passed away from the old river, a few enthusiasts only keeping the sport alive."